Red Bells and the Bushmen

by

Phil Mershon

602 218 1649

Story is like the wind. It comes from a far-off place and we feel it.

—Motto of the Bushmen of the Uitspan Hunting Ranch

Part One

The Power of Scrambled Eggs

Chapter One

Bert Kerns died over the third weekend in June, 2024. He had tuberculosis, but it wasn’t the disease that killed him. He turned up sitting beneath the big old oak tree in the center of Pickaway Square Gallo Port Korea

I hear it isn’t all that odd for a friend to feel responsibility for a loss like this, in particular when the dead guy was as good a chap as old Bert was. I know that sounds corny as a cob, but he really was a friend of mine and he never hurt a soul on purpose. Well, nobody unless you count that no account ex-wife of his, a right tramp everybody knew as Judy Booty. He caught Judy Booty cheating on him with Royal Wunk, the television repairman from over in Washington Courthouse. That woman hadn’t been much to look at in the face, that was for sure. Like you might guess, she had a derriere that never seemed to end, which was maybe the best thing you could say about her. Oh, she was a clever one, don’t get me wrong. Bert was fond of saying that Judy had brains she never used. He’d grin when he said that, knowing you could take it two ways. In any case, I’m here to tell you there’s nobody could really blame my friend for throwing Judy out in her skivvies after she went and broke his heart the way she did with that shiftless stack of dog vomit Royal Wunk. If there was ever a guy who had a name stuck on that fit him like a Playtex glove, Royal Wunk was just that guy. He wore the tops of his pants so high they almost reached his underarms, he spray-painted the top of his head the same color his hair had been when it was thick back in third grade, and he had teased me uinmercifully when we were kids—teased me about my clicking when I spoke, not so much a speech impediment as a family tradition. He’d been in kids shoes back then. These days that balding bastard wore a pair of fancy leather boots that pretty much announced he was a big turd in a little bowl. When you saw last’s night’s spinach still clinging to that Rotarian Club smile of his, you knew his name before he ever told you, just like you knew that someday somebody was gonna catch him in bed with another man’s wife. Then you’d wonder why the dopey gal would be caught dead with a hump like Wunk. But I’m getting off the subject again. Damn senility. Well, like I say, Bert was a hell of a good guy in spite of punching that TV repairman right in the stomach and throwing his idiot wife out in the cold. She ended up selling—and this is no joke—seashells by the seashore two states over on Virginia Beach

Bert walked up to me as I was sitting over at Elroy’s Sunoco Station. I saw him coming from the corners of my eyes and I could tell right away that something bad was up with him because it wasn’t like him to butt in when I was catching up on my reading. I read. I’m a reader and I read what some people say is a lot and I don’t give a good God damn because I enjoy myself and what business is it of anybody what I do with what little spare time I have left? I’m sorry to be so wound up about this and I really need to stop digressing. It’s just that there are so many details that connect to one another and the story itself is an amazing thing and I want to set it out just right. Okay, alright, I’ll try to rein myself in and stop wandering. Well, this particular day of which I am talking, Elroy was out back taking a leak and my nose was buried in a book of baseball wisdom by Yogi Berra—Him? Oh, he was a dead and retired baseball catcher who had all kinds of clever things attributed to his wit, most of which he never actually said, but somehow it pleased people to give him credit—and I was just getting ready to spit out a watermelon seed that was threatening to choke me when up comes Bert with this look plastered on his face like a man who just lost his best friend. Under normal conditions, he would have seen me reading and rolled his eyes, cleared his throat, sat down and waited for me to take a break. But not this time, no sir. His shoulders were slumped almost down to his ankles. His surly smile was gone and in its place was a turned down horseshoe of a frown. His fingernails were digging into the flakes of skin on his arms and to put it short and sweet, he looked like death warmed over. I nodded hello and felt a chill in my bones as he took up a chair and grabbed my page-turning hand in one of his own. Those thick, long yellow fingernails of his dug right into me. His nails were so thick that he actually used them as screwdrivers when the need arose, which wasn’t really all that often. They were so thick it took a pair of tin snips to cut them.

I gave him a solemn look that I hoped said it had better be important, what with me reading this book of pure specific genius and general foolishness. I regretted giving him that look almost immediately. He shook the hand that held mine and told me he had just come from Doctor Seitz’ office. Rocky Seitz grew up here in Circleville just like most of us old farts did, even though Rocky himself was a good bit younger than his patients. He did real well in high school—salutatorian, I think it was—and he got himself a tennis scholarship, of all things. He went off to study medicine at Ohio State University in Columbus Columbus

He said, “Ain’t never going back to no doctor again.”

“That so?” I asked him, steeling myself from what looked to be some sort of fatal news. When somebody comes back from the doctor with a big old smile and you can hear the laughter in his voice, you don’t mind so much asking how things went. When a guy’s eyes are sparkling, it means he either had a good dose of painkillers or the news was positive. But when the look on the guy’s face reminds you of the Balkan Death Camps and his voice sounds like something calling out from the La Brea Tar Pits, you know it’s gonna be bad news and you try to brace yourself so that you can show sympathy and yet try to be optimistic for the other fellow’s benefit. All the same, I blurted out, “What’d he tell you? Cancer?”

“Naw, it ain’t cancer.”

“Brain tumor?”

“Naw, ya dumb hick. Ain’t no brain tumor.”

“What the hell is it, Bert? Pink eye?”

Bert said, “No, wise guy. You know what he told me? I’ll tell you right now. He told me I have TB.”

I have to admit I felt a little relief, even though at the age of eighty-eight you can’t take any news like that for granted. Before I could say anything about it though he squeezed my hand and told me how good it had been to know me all these years. I had to smile a little at that and broke into one of my mini-sermons, which by now you may have already come to suspect happens far too often. This is the kind of situation where you are secretly glad the other fellow is overreacting—glad, I say, because it puts you in a position to make the guy feel better. Bert was my friend. I loved the guy. We had grown up together, gone on double dates together, worked in the same Bulk Plant together and gone down and applied for retirement together. He was as fine a friend as I’d ever had.

I told him that tuberculosis wasn’t fatal. It wasn’t some death sentence. They had vaccines and antibodies and all kinds of cures for that these days and while it wasn’t good to have TB, it sure wasn’t the bad news his face was making it out to be. But old Bert, he just looked at me like I was the world’s biggest idiot and said that he didn’t plan to spend his golden years laying up in some treatment center and that he reckoned this was all God’s way of settling the score with him for the way he’d chased off Judy Booty forty years before because of her infidelity with Royal Wunk.

Now, truth be told, I wasn’t all that thrilled with Bert sitting there breathing on me and holding my hand that way, what with him having a case of TB which, despite all the modern day treatments, was still, last I heard, contagious in the extreme and not a nice thing to have. But hells bells, he was my best friend, so when that’s the situation you don’t worry about how it might affect you. You don’t worry as much as you would if it was some traveling salesman trying to unload Bibles and coughing up a lung all over you. I just pushed the thought about me getting sick and dying to the back of my brain and gave my friend what I hoped was a look of two parts sympathy and three parts wisdom. “Bert,” I said. “This ain’t the end of the world. Worse thing’ll happen is they’ll make you spend a week or two in the Berger Hospital and you’ll get one of them pretty candy stripers to give you a sponge bath every day, you lucky bastard. You’ll be back to boring us with your old stories in no time at all. Come on, what’d Doc Seitz really say?”

Bert went on looking at me like I might have just dropped in from some planet where people didn’t have enough sense to recognize bad news when it was staring them right in the eye. He sighed like it was causing him considerable discomfort and said, “He told me all that stuff you just said. What you and Rockwell Seitz don’t comprehend is that it’s the idea of that bad stuff buzzing around inside of me. When was the last time I was sick, Moe? Huh? I’ll tell you when it was. I ain’t been sick a day in my life. That means that if I’m sick now sitting right here next to you today, then that has to mean something. It has to mean something bad. Naw, I’m not going to take it. No way in hell. I’m not that kind of guy. If I still got this bad thing in me this time tomorrow, well, I know exactly what to do about it. I know just what to do.” Then he cleared his throat and I could hear—man, I could smell that sickness on him—and it was right then that I knew what I needed to do to help my friend. But the truth is I was scared. I was scared of the power. I was scared because the power was a new thing to me. I hadn’t known for sure that I had this ability until about two weeks before Bert came up that afternoon and I should have done something a lot more substantial than just telling him he was overreacting. Like, for instance, I should have done a better job of hiding my Phenobarbital. It’s too late now, of course. Bert is gone like a book you know you want to reread and can’t figure out where you left it. You look everywhere and you check with everyone you know but you just can’t find it. Then you curse yourself because you forgot to write your name in it. So now he’s gone and I’m here to deal with the future. And I’ve seen the future. I’ll tell you about it.

On June 1, 2024, about two weeks before Bert Kerns passed away, a big mess of things started happening that changed life as we used to know it on this here madly spinning orb. Most of you probably think things have always been the way they are today, but I’m here to tell you it all used to be different. The way it went was like this. Just a few breaths after midnight, June 1, Ohio

The news of this situation came to me over the talk radio station, the one I like to listen to as I’m trying to get to sleep at night. I listen to it almost every night even though you can’t believe most of it any more than you can the slop that comes over the TV set downstairs. It’s almost all a bunch of trumped up horse manure, everybody says it is, everybody knows it is, and yet we all keep right on listening and watching. All the same, this was one hell of a claim the radio announcer was putting out, so I turned the damn thing off and walked down the hallway in the dark and by touch I was able to find my old Moon Copter Telescope. What I knew about Jupiter at that time you could put under your pinky fingernail. I blew the dust off of it—the scope, not my fingernail—and got back over to my bedroom window. The fool on the radio had said that Jupiter was visible just to the left of the Moon. I saw what I knew had to be the big planet blazing up in the smelly sky. I lined up the Moon Copter and after fiddling around with it for a while I zeroed in. I hadn’t used the Moon Copter Telescope in a long time—How long had it been? Had it been during the first moon landing back in 1969? Yeah, that was it!—but after a few minutes I found the planet’s surface. Sure enough, there was just a big swirl of green and white where the Great Red Spot had loomed for centuries. I’m the first guy to admit I’m no astronomer, yet all the same, I knew the Red Spot had been there and now it wasn’t. It was gone. Puff.

That was the first thing and as far as I had known it was going to be the last. I mean, hell, it was more than sufficient. I put the scope away and treaded down the staircase. No way was I gonna get any sleep anyhow. I went to the refrigerator and took out a couple slices of bologna. They tasted foul as spoiled mincemeat so I washed them down with a glass of iced tea that had just started to turn bad. I spat all of this out and went into the living room and dropped down in front of the TV. I flipped on one of the dozens of lying news stations, planning to wait out the night. Aches and pains always hurt worse at night. Nobody knows why.

The next bizarre thing happened about two-thirty that morning. A barrel-chested bug-eyed bastard was on the TV in a shirt and tie and a two hundred dollar haircut screaming about how cosmic rays had caused the U.S. Army to turn gay except for a few Lieutenants who had presciently locked themselves in a titanium shelter. This was the kind of nonsense that passed itself off as information in those days. You’d sit there and nod while you ate chicken soup in your pajamas, knowing full well that in a couple hours time this same lying newscaster would come back on the air, shaking his head and sadly reporting that while this particular rumor had been disproved (and didn’t that just go to show you how you couldn’t trust people these days, especially what with all those cosmic rays beaming down on us? Slurp, slurp), but all the same a bunch of two-peckered goats were sodomizing one another in the middle of the Potomac River and wasn’t that just as bad if not worse? Oh, it was a freaky time to try to sort out fact from fiction, so even with the earlier proven news about the Great Red Spot, I was a bit doubtful of this man’s report that every black person of either gender aged sixteen years and above had suddenly developed a purple ring in the center of his or her chest and within that ring sat the thin lines of a perfect acute-angled triangle, this one the color green.

I unsnapped the top two buttons of my flannel shirt and peeked underneath. There it was: a flat purple circle with a green angle jutting out of its middle. I saw it and still did not quite believe it. You get so accustomed to being lied to that sometimes the truth—even truth that stares you in the face—is hard to believe. A man’s eyes are not always the best indicator of things, although usually that is all we have to go on. But I was clinging to the notion that this change was somehow unreal. After all, the guy on the TV was a semi-professional liar and I had taken a hell of a lot of illegal drugs in my life, some of them earlier that evening, so there was really no telling. I knew the TV man was a no good liar just like he probably knew it himself, just the way his mother and wife and children knew it, all of them sharing in the shame when they weren’t buying things they didn’t need at the store to take their minds off the embarrassment. All the same, I clicked the remote to the Telephone position and scanned down until I came across the name of Randolph Mosley. It was late. I knew he’d be unhappy. But I called him anyway. I screwed up immediately by calling him Randy. He had told me forty-eleven times that “randy” was an adjective and “Randolph

Things were kind of quiet for a spell then, except for the bad news that Bert was gonna lay on me but hadn’t yet, when just before dawn on June 21, not so much the longest day of the year but rather the one with the most daylight, Earth’s northern polar ice caps—which had over the preceding three decades shrunk to half the size that they were back in 1984—began to rebuild, and by the end of the night they were back to the dimensions they had possessed toward the end of the twentieth century. That was pretty important because of all the concern about global warming. I know today we take climate change for a pretty obvious condition, but for a long time people actually argued about whether it was some sort of political ploy or science fiction nightmare dreamed up by environmentalists so they could get paid to do research on it. So when the ice caps started to reform themselves after decades of thawing out, that really blew the minds of everybody with minds left to blow.

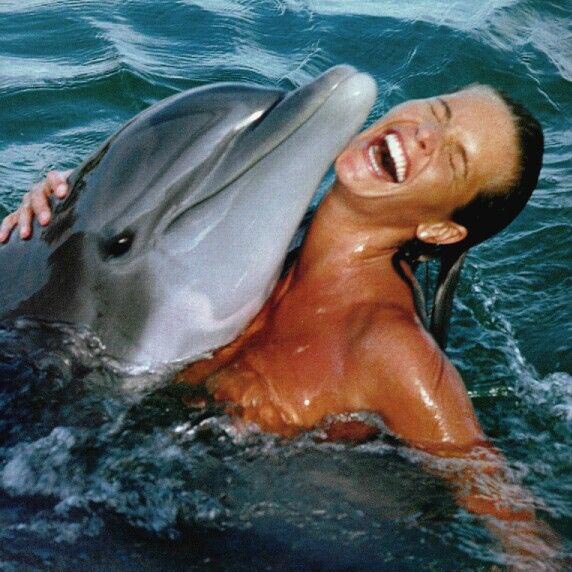

The weirdness continued. The physiology of dolphins, as of nine a.m. that first summer day, mutated so that all ten million of those that hadn’t been exterminated during the Big Dorsal Purge of twelve years earlier woke up to find themselves with tiny legs and external lung sacks that somebody said resembled the breasts of the well-endowed President of the United States and which enabled the intelligent sea creatures to spend time on land for short durations, during which water breaks they appeared to be plotting some type of shoreline coup d’etat against the erstwhile leaders of the planet, not that anybody seemed to mind very much. I had felt very bad about the Big Dorsal Purge because dolphins had always struck me as highly pleasant creatures, much more so than the orangutans from Borneo that some folks said were ninety-nine percent similar to humanoids, at least before those orangutans took over Plymouth, Michigan, and then the story changed to how human beings were ninety-nine percent similar to the great apes.

All this was a lot with which to come to terms. Some wiseacres used to say, “Change is good” with a perky lift on the word “good,” the kind of ageless balderdash you’d expect in this spinning nuthouse world of ours, despite the obvious fact that change is actually neutral and it is the results of change that are either good or bad or both. So I was reeling from the aftereffects of this new pack of sensations when just before noon that fateful day, I was stricken with the power to alter things without the use of medicine, psychotherapy, modern tools, electricity, radiation, or any of the other methods in common practice in those days. All I had to do was clear my mind of excessive nonsense (easier said than done), focus my thoughts on what it was I wanted to see happen, get all worked up emotionally, and within a few seconds that thing would exist in just the way I wanted. If I had told anyone about this, chances are they would have booked me a small room in a big hospital. Well, it was odd, I’ll admit, but not any more peculiar than all the other weirdness going on in the galaxy around the same time.

It came about just as sudden as all the other changes had come about. I was having my breakfast the morning after all this other stuff happened. I was over at Lucado’s Restaurant on Court Street—I like Henry Lucado’s scrambled eggs and toast—it wasn’t exactly Italian fare but then again Henry was about as Italian as the Black Panthers—and I was reading the late edition of the Herald newspaper—one of the few papers left in the state—when Henry comes over to my table and says he’s going to be closing up early today because, the way he figures it, the world is coming to an end and there was no reason for him to miss it just because of business that he didn’t care about anyway. At that time a lot of people obsessed over the notion that we were living in the “last days.” In fact, the fretting fever about the end of time was so pervasive that you had to watch what you said sometimes or else certain alarmists would misconstrue your meaning. Like, you couldn’t say, if you were all exasperated, “If it’s the last thing I do,” because if you did, it could be taken the wrong way and people would say you were hinting that the end was near. Another expression you had to stay clear of was “What’s this world coming to?” and you never wanted to say, “That’s his cross to bear.” Words with apocalyptic or even religious overtones could send even reasonable people into screaming fits of paranoia. So anyhow, I looked up at Henry and smiled patiently since there wasn’t much else I could do at that point. He smiled back as he sat down beside me and leaned his mouth in toward my ear and whispered, “I put something special in the eggs this morning. Everything is just right. You won’t thank me today. Some day you will. Enjoy.”

I thanked him just for spite and with that he got up and hung the CLOSED sign in his window and never did return to take it down. I was hungry as a pothead, so I ate the scrambled eggs and locked up for Henry. I wasn’t in any hurry to go back home because it felt like the conditions Henry had hinted at must have been just right at that. I patted my stomach, impressed with my condition. I felt downright strong and confident and at peace with myself and everything else in this madcap world. I had a buoyancy in my heart that had not been there for a long time. All the same, I didn’t really think of things as being different inside of me. I just felt nice and full. I went outside and smiled up at the brown clouds drifting between myself and the noonday sun. I hiked up my pants and decided to walk off the breakfast.

I didn’t get much more than twenty feet from the back door of Lucado’s when I spied Old Lady Maxwell hobbling down the sidewalk with that ugly old walker of hers pushed out in front of her trembling legs. A baggy flower-print dress hung from her knobby shoulders down to just past her shaking knees. A pair of nylon stockings were rolled like baby elephant skin at her ankles. Her big black shoes looked like something an orthopedist had tossed in his trash bin. She had a pair of reading glasses hanging by a chain around her neck. If I’d have looked closer, I might have seen her hanging from a chain, that’s how worn out she appeared. Poor old Margaret, I thought. How in hell was she going to survive in this unstable world where dolphins invaded state houses and planets changed complexions and people like myself grew tattoos overnight? How could a person even talk to her about those things? If I had walked over and asked what she thought about the North Pole coming back to life, she would have wet her drawers right there on Court Street. She had gone a bit soft in the head in the last few years, some days remembering details the rest of us had forgotten and other times not remembering where she had left her front door. But son of a gun if she hadn’t been some kind of beauty back in high school. Who am I kidding? She had been a lot more than beautiful. She had been the kind of girl who didn’t get by only on her formidable looks but rather the kind who also knows the answers to the algebra problems and who looks forward to French class and who helps out her less pretty and far less gifted girlfriends with their homework and who never one time acts snotty about being a clear cut above most of her classmates. Yet there she was, inching along the sidewalk, having one hell of a hard time making it off the Court Street footpath to the Howard Avenue

I still had that image of her from those teenage days of long ago in my mind as I walked over to lend her a hand, not that I thought for a minute she’d let me. Even as a high school senior she had been independent to a fault, sometimes even getting herself in danger when tough guys sniffed around and she’d get scared. She’d get real scared, but she never cried out for help. She’d just run on those perfectly pronated legs of hers.

What with her being such an independent type, I’ll admit to a little nervousness as I laid a hand on one of hers, one that gripped that walker. I didn’t want to take her by surprise, but she was half deaf so it was hard not to catch her a little off guard. She looked up at me with a most terrified countenance. For a second I thought maybe I had imagined that spasm of fear because it left her eyes in a flash and what came over those witnessing orbs was the look as she had been seventy-odd years earlier, back when she soared with the wind at her back, when the biggest problem she’d had to worry over was whether she’d go to the dance with which one of the twin Dover brothers. God, she was beautiful. She looked up at me. I gave her what I hoped was a reassuring smile and as I did, that bend in her back, that grip on the spine that taunted her with failed dreams, with disappointments just dissolved and dispersed, went away clean and was gone, a lot like the way that Big Red Spot vanished from Jupiter hours earlier. Her frightened look faded as she straightened up and as she unstiffened I swear on my birthplace that those track lines in her face and on her hands and arms—those lines that had screamed she would never find her pot of gold at the end of the rainbow and that only fools tried—those bastard lines lost their power and dissolved, revealing her as a young woman, as the young woman inside her that had refused to die. Somehow she had kept a tenuous hold of her earlier self. Somehow, despite all the television lies and screaming headlines and threats of doom, the girl in her had stayed on life support. Maybe this was the young woman I remembered or perhaps it was the woman she had always been deep down. You can never trust your recollections one hundred percent since your own fantasies color things one way and reality never has a fresh paint job. Whatever the case, she was a damned sight closer to her young beauty than she had been a minute earlier.

If I couldn’t put faith in my eyes, I sure could hear it in her voice. “Good morning, Maurice. You’re looking well today.”

It was as if some rare bird had flown into my frame of vision and displaced Margaret Maxwell with this young female we’d known long ago as Margie. For some people maybe it’s a rainbow that sucks breath out of their lungs. Maybe it’s a baby’s first giggle or a sunset or a rookie hitting a grand slam in the bottom of the ninth. For me, it was looking at Margie Maxwell as she looked back at me, her eyes wide and unwilling to blink. “Can’t imagine,” she sang. “I cannot imagine why this walker is here. That is the last thing I’ll ever need.” As she breathed out those words, she let loose with a laugh. Lord, it was a laugh we have all heard in our young and old days alike. It was the laugh of a girl up on the hill in the throws of indescribable cheer over nothing more or less important than the grasp of the universe around her. It was the laugh of a child sitting next to his father on a rollercoaster ride as the dad turns green with nausea. It was the laugh of lovers tickling one another on the sofa during a solemn moment in the motion picture they are watching. Margaret—Margie—laughed just like that and then went on her way up the incline toward her house, leaving that walker alone on the sidewalk beside me. I still freeze in my bowels when I remember the transformation.

I stood there on Howard Avenue

I looked up into the big, late afternoon Ohio

I didn’t know what else to do, so I turned around and walked back down Court Street, hands shoved deep in my pockets, head a little low, mind absorbed with trying to figure out if what I’d just seen had really happened or if I was at long last giving in to the pangs of senility, a concern I’d been dealing with off and on since I’d retired from the Bulk Plant twenty-three years earlier. If a man can’t stay busy after he gets his gold watch, he’s apt to go crazy pretty quick. A lot of guys do just that. Rocky Seitz told me way back last year that I needed to keep my mind occupied or else he’d stop by one day for a visit and find me counting my toes. I had a big laugh at that at the time, but the truth was he knew what he was talking about because going nuts kind of ran in my family. Oh, I knew about Ma going off for long walks out in the woods back of her house after Pa had run off with that decorator from up Columbus

I never had any brothers or sisters, at least not in the sense of them coming from my Ma or Pa. But I sure had a mess of goofy relatives, mostly on my mother’s side. One of the craziest was Jim Shoemaker. He was my mother’s brother. I called him Uncle Jim. He worked for the railroad. That was a means of transportation that ran on steel tracks and always seemed like it was running later than you wanted. Uncle Jim was what they called the engineer. It was his job to steer the train, which was kind of odd since the train was on tracks, like I said. If you were moving, you could only go backwards or forwards. It didn’t seem like that complicated a job to me. Well, Uncle Jim, he liked to walk around and talk to the passengers while the train was in motion. He wanted to make sure everybody was having a pleasant ride. They would have probably had a much more pleasant experience if Jim would have stayed up front and just tended to his business. More than once he rammed that railroad train right into the rear end of the caboose of a train that had stopped ahead of him. After about the third or fourth time this happened, the railroad company had to let Uncle Jim go, meaning they fired him. He started hitting the bottle pretty heavy after that. The last time my family saw him he was screaming at the door of an elevator in a big office building. He kept telling the elevator door it was going in the wrong direction. Some soft-spoken men in lavender suits came along and we never saw Jim after that.

At the same time there had been Aunt Nettie Shoemaker. Now she was one for the books. She had herself convinced that every woman in Pickaway County

So I was more than a little upset that afternoon as I was moping my way down Court Street, worrying that just possibly the Mad Hatter was about to hang his jangling cap on my head so I could join the tea party. I was so beside myself that I walked right past Henry Lucado and he must have called my name a bunch of times before he finally took me by the sleeve and gave me a little shake.

“Moe! Moe, for God’s sake, you look like a ghost. Didn’t my breakfast sit well with you?”

I looked hard into his eyes, trying to figure out what the hell he was talking about. My scalp tingled and my blood sugar was scraping bottom. What had he just asked me? Breakfast? What? Oh, right, right. He had served up some scrambled eggs that morning, sure, just like half the mornings over the past twenty some odd years. Right, I knew that. Where was my head? “Henry,” I said. “Your eggs were just fine. Just fine. No, I just—Henry, I’m getting old.”

He dropped my sleeve and said, “Boy, we’re all getting old. Beats hell out of the alternative, huh?”

I was gonna tell him I’d heard that line about as often as I’d eaten his eggs. His eyes caught a stray ray of wanton sunlight, though, and the old proprietor looked like he was trying to say something with those eyes instead of with his mouth. I’d had enough strangeness for one lifetime. I was feeling sick, so I made to get back to walking on when he reached out and took me by the shoulders. He said, “I picked you for this project and you can’t let me down, damn you. Now you listen here. The universe is messed up bad. Been getting worse and worse ever since I can remember. Now things are breaking apart. You know it and I know it. A man can’t hardly see the sun these days. Pollution’s so bad a man’s got to be a freak just to survive. Schools are shutting down. The police lock up jaywalkers while a bank’s getting robbed right behind them. It’s the universe, Moe. It’s screwed up. We’ve seen it coming for a long time and now it’s here. But there’s always a way out. Always. I may have been wrong, but I picked you. I don’t exactly know why I picked you. I knew somebody had to be selected. I was staring out the window, trying to find the planet that lost its spot. Jupiter? Yeah, that one. I was looking for that with my pair of binoculars and all a damned sudden: WHAMO! The image of you filled my head, Moe. Soon as that happened, it made perfect sense. It had to be somebody a little twisted, but somebody most folks like. Somebody who sees the world for what it is and not for how he wants it to be. Besides, you ain’t all that crazy. You got more sense than your mama. You, Moe. You have been selected. Now you need to get out there and do what needs to be done. But don’t you go questioning yourself. You know what to do, boy. Get on about it.”

With that he let go of me, his eyes still twinkling, his mouth nice and still. He let me go with a little push and eked his way up Court as if he had some place to go. I shouted after him, “What am I supposed to do? What are you talking about, Henry?” He must not have heard me.

Henry Lucado. What did I really know about him? Was he crazier than I felt I was? How did I feel anyway? Blood sugar back up, tingling all gone. I felt great. My mind was at peace. The harsh air no longer burned at my lungs when I took in big breaths of air. The skin on my arms had a radiance that I had not seen there in years. My joints didn’t hurt. They felt limber! My spine actually felt artful and strong. Yet I was definitely the same old Moe Washington

The dusty shops selling souvenirs and liquor and microwave meals stared back at me without comment. The hardware store across the street boasted a sale on roof nails. Some woman named Tiffany wanted to paint fingernails. The Western Auto store was doing a brisk trade selling bicycles. Tiny Mitchell’s Realty Market glared out with a quiet hostility, the opportunities for things such as homes, businesses and other forms of realty having shifted up north Columbus way, to the extent that they existed at all. Tiny Mitchell looked up from his desk just as I was glancing in through his window with the painted words GO “BIG” WITH TINY MITCHELL forming an arch across the glass. Tiny loved that window sign. He must have washed and shined that glass five or six times a day to keep it as sparkling clear as it was. I was instantly sorry he had seen me. If I had been on my game I would have crossed to the other side of the street before I’d gotten this far. But he’d seen me and he’d seen that I’d seen him. He waved a remarkably enthusiastic and insincere hand at me. I opened his door and a little bell clanged. Tiny smiled at me. I smiled back. He motioned the chair across the desk from him. I pulled at my pants knees and sat down. He offered me a cigarette and I declined, although I don’t know why. If there was ever a person you wanted to blow smoke at, it was Tiny Mitchell.

“Glad you stopped in, Moe. Glad indeed. How the hell you been lately? Can’t recollect the last time we had you over for Pinochle.” There was a reason he could not remember. The reason was I had never played Pinochle with him or anyone else. I didn’t know the first thing about the game. I heard it involved a deck of cards. “Been wanting to talk to you for a coon’s age, Moe! How’s the world treating you?”

“It’s treating me about like a baby treats a diaper.”

Mitchell snorted and roared as if I was Richard Pryor in spite of the fact that he set me up for that line every time we met. “Moe, that doesn’t sound too good! No, sir-ree bob! Maybe I can clean up that diaper for you a little bit. You want a shot?” He tilted his head toward the tequila bottle standing proud and strong on the edge of his desk. I shook my head.

“Okay, Moe, let me get down to cases. I know the real estate business in Circleville hasn’t exactly been like fireworks the last few years and home prices are falling like, like, well, like I don’t know what.”

“Like a virgin’s pants on prom night?”

My suggestion was met with another round of snorts and roars. I should have been charging by the laugh.

Tiny cleared his throat and went on. “Okay, Moe, the thing is that there is always an upside to these things. Prices drop one place, they go up somewhere else. What was it my Daddy used to teach you all in Physics class? For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction? Okay, Moe, that’s how it is in this business too. Prices drop one place and go up some other place. Like your place, for instance.”

I stared at him. Sometimes a man just can’t believe the way other people think. I said, “You hear about all the strange things that have been happening, Tiny?”

“Strange?” he asked, looking as if the word made him uncomfortable. Strange might mean unmanageable and that, of course, would never do. “What do you mean, strange?”

“I mean the way Jupiter lost its red spot the other night. In less than half an hour. Ice caps rejuvenating. Dolphins taking over. Oh, and Bert Kerns died.” I gave him a hard look with that last one.

Tiny poured himself a shot and downed it. His face came up grinning. “That’s something, all right. But you know what I always say, Moe? I always say that I’ve got my hands full dealing with local real estate. Ha ha ha ha! You get it?”

I decided to take one of his cigarettes after all. If he could use the bottle of tequila as a prop, I could use a smoke stick. “Then there’s always the orangutans,” I said. “The ones fighting the dolphins in taking control of world capitals? I’m sure you’ve heard.”

He smiled. “Sounds like a game of Risk, huh? World domination! Ha ha ha ha!” By now his laughs were coming in fours. “But we were talking business, weren’t we? Yes.” He lit my cigarette and said, “We were talking about your place.” I could have told him the lepers were raping his bulldog and he wouldn’t have blinked.

I was halfway into hating the day of June 21, 2024. Too many things were happening and they were happening too fast for me. The day side of this twenty-four hours couldn’t pass by fast enough for me. I asked him exactly what he was talking about.

He looked at me the way a working girl looks at a young rich guy with a grin in his pants. He said, “It’s possible that I know of somebody that might be interested in buying that place of yours. Yes indeed I might.” I exhaled smoke over his head. He still didn’t blink. I wished I could pass wind. “Okay, Moe,” he said. “We been friends a long time, so before you tell me you’re not interested, just hear me out.” We had never been friends. His daddy had been a jerk and a lousy teacher to boot. Most teachers had had the decency not to laugh at the clicking I had made when I talked. Not Mr. Mitchell, though. He found the whole thing hilarious. I guess he passed his sense of humor onto Tiny. I knew what this dirt hole said about me behind my back. He went on, saying, “You got no family left here in town, right? No heirs waiting in the wings to suck dry your last dollar once you depart from this here mortal coil? No one to claim their so-called right to your estate, am I correct?”

I admitted that he was. I had been feeling so good for a while there.

“Okay, Moe, what I’m getting at is this. You got five acres plus your house. Now just suppose you were to find yourself sitting pretty with enough cash money on hand so that you could do any damned thing you wanted, huh? Go to Europe ? Go to Africa ? Hell, just fly around and around and stop wherever you wanted and stay in the nicest daggone hotels this side of the Taj Mahal. You’d have to fight off all those fine looking young gold diggers, but that’s not such a bad problem to have when you think about the amount of time you have left. No offense now Moe, but facts is facts, just like they say. You ever give any thought to what I’m saying?”

I nodded. “You know where I’d really like to go, Tiny? Where I’d like to spend what little time I have left?”

He leaned forward and cocked his head in the most sincere pose I have ever seen in a thief. “Tell me, Moe. Where?”

I said, “I would like to spend the rest of my life in the Federal Corrections Facility down in Chillicothe

My words were met with a final burst and spray of laughter. Ha ha ha ha. When he finally pulled himself together and stared back at my solemn face, he asked me why in the known world I would ever want to visit such a place.

“I would enjoy doing a life sentence for shooting you right between the eyes, you stinking, rotten, barnyard hayseed. Why don’t you tell that to the ‘somebody’ who wants to buy my plot out from under me?” With that I got up and walked out of Tiny Mitchell’s Realty Market. Damn, I was mad. I hated to get that angry, but it was hard not to when talking with a polecat of that sort. But then the strangest part of the whole scenario—and the reason I mention it at this point in the story—is that just a second or two before I slammed the door to Tiny’s office, his big glass window exploded out onto the street, jangling and crashing and splattering in a cascade of splintered color as pretty as anything I had seen since the inside of my kaleidoscope when I was a kid. By the time the last sliver had struck the sidewalk, Mitchell was out that office door of his, holding onto his head, shouting, “What’d you do, you crazy old bastard? What in hell’s wrong with you, you clicking freak? You break my window? You know how long I’ve had that window? What am I gonna do for a window? Why’d you do a thing like that to me? My winnnnnnnnnnndooooowww!”

I told him I didn’t do it, that I hadn’t had a thing to do with it, and that he was nutty as a fruitcake for even suggesting such a wild idea. But deep down I knew I was lying. I had done it. I just didn’t know how. All I knew was that it had something to do with polar ice caps and morphing black people and vanishing storms in outer space and land-bound dolphins and Henry Lucado’s scrambled eggs.

Chapter Two

The spring wheat fields shivered that night beneath a half moon of indifference. Maurice Washington would not have known what to call the long arm of frigid air that wafted along the powdery topsoil, lifting fallen pollens and setting down dry dust. The dark side of the half moon occupied itself with peeking out at the far away planet that had passed that way infinite times unchanged. Cool water ponds chilled beneath the twitching night sky, freezing over and thawing, freezing and thawing, many times throughout that long night of oblivion. Raccoons chattered, restless, nervous, sensing a shift in the landscape, with nowhere safe to scurry. The rabbits that hung around Maurice Washington’s backyard, down near the spoiling carrots that had been there since last fall, forgotten about and slimy, those rabbits nibbled on one another’s ears in silent frustration, the wind filling their furriness with an anticipation they did not recognize. Smells unnamed by scientists floated in and out of opened windows in the small town and across the flat country surrounding it. The farm bureau scientists, had they been out that particular evening, would have dismissed the readings their equipment blurped out. Nothing that night in Circleville and in a thousand towns just like it was the way it had been, nothing moved with the earlier certainty, nothing yawned with the former complacence, and nothing reached with the same expectation.

One thing in particular had been changed in the wake of these cosmic reshufflings. The red bell peppers served in Henry Lucado’s restaurant had mutated. To the taste they offered a sharp sweetness, somewhere between the lick of an apricot and the cold metal of a straight razor. To the eyes the redness blazed in its proud audacity, even under the half moon light. The seeds inside trembled with desire. The taste came to one’s mouth before the skin of the fruit was even cracked. The potency of the fruit swelled wild and untamed, so confident in itself that hopping creatures and those that crawled alike were unable to so much as approach the peppers as they grew in Marybeth Gowan’s farm. Powered by their own intent, they existed for the humans alone to experience. Henry Lucado, the enthusiastic restaurateur who had commented on their appearance had been privileged with the first taste. It had stung him like a wasp in the mouth, one that refuses to give up until at last it is swallowed. His sense of awareness—one which was far more reality-based than his neighbors ever sensed—was ignited and in an instant he had known he must select one person to protect the world from the awfulness that loomed nearby, taunting the frightened people and animals in its invisible wake across the land.

He had selected with care. Moe Washington

Henry got as far as the county line. His 2019 Mercury Stabilizer blew a rod and the electric motor sputtered, spat and made more noise than the worst of those old internal combustion engines of not so long ago. Then the stupid thing drew back and just heaved one last time before two of the factory warranteed wires heated through their rubber coating, connected, caught fire, and launched a spark back to the reserve tank of compressed natural gas. It took maybe one long stretch of a second, Sheriff Radcliffe told us, for that whole little car to turn into a huge fireball, leaping something like twenty feet in the air and landing just inside the home track of the Pickaway-Ross county marker.

It was one thing to think about colossal abstractions like Red Spots and ice caps and sea mammals or whatever. It was a whole different kettle of fish, so to speak, for two people we all knew to up and die so close together. My folks had been Presbyterians, so I wasn’t a religious man, but even I was beginning to ask myself questions about coincidence and fate. Sometimes I get lost in thought that way and this time I was staring at Elroy without knowing it. He snapped his fingers in front of my face and asked me if I was checking out his derriere. Elroy truly prided himself on being the local comic. Timing is everything.

Elroy topped off the sheriff’s tank with Ethanol. The Sunoco proprietor was actually a corn farmer, but he figured he’d cut back on his expenses (or add to his revenue, I could never remember which) by franchising for the Sun Oil Company. Sunoco paid his processing costs and even sent out engineers and inspectors from time to time to make sure El didn’t need a hand, which he didn’t. It was a sweet deal all around and pretty much every Ethanol-fueled automobile driver in the area patronized his station. The state law said that Ethanol had to be pumped by a licensed dealer, so Elroy got himself a license and because I liked to hang out there and read my books, he got me a license as well. It didn’t take any special talent to fuel up a rig with Ethanol, any more than it had to gas up with gasoline. But who was I to argue? I pumped and in return I could take up space and chat with folks who needed a fill-up and drink all of Elroy’s soda pop that I could handle. And let’s not forget my major joy in life: reading. I actually gave the matter some thought and it came to me that reading a book on baseball was just plain inappropriate at a time like this. The only reason I really considered it was because I had been sort of angry with Henry for “selecting” me. I was angry with him for dying without explaining himself. I was angry at him for dying, period. A man doesn’t have that many friends. Good ones are even rarer.

Sheriff Radcliffe hadn’t much more than left the station when Bert Kerns came up with his news about the tuberculosis. After he moseyed away, I sat and thought about what had been happening and what my responsibility to improving things might be. With Henry Lucado dead, I was gonna have a hard time finding out what he’d put in my eggs. But by gum he had added something. He had “selected” me for something. He had chosen me because things needed to be fixed and because, even with a family history of silliness, I was still somewhat acceptable to the local folks, excepting an overfed realtor with a broken store front window. Looking back on it, of course, I wish I had kept a better eye on my barbiturate stash. If I had, well, I don’t have to spell it out. How does it go? “If things were different then they wouldn’t be the same.” That was in Yogi’s book.

Things were a mess in the world, there was no doubt about that. In the New United States alone we had gone through three Presidents in the last two years, one dead from an assassination, his successor impeached and jailed, and the current commander in chief a nice enough woman but the leader of a political party with about as much credibility as a chain smoker in a cancer ward.

And speaking of the government, some well-intentioned clown a few years back decided that public school children weren’t learning enough in twelve years and so what we needed was not so much better schools but ones that kept students for an additional two. As it turned out, it was hard enough to convince young people that there was any value in going to school at all beyond the tenth grade; the notion that most of them would be twenty-years-old before they graduated was just too much and the immediate result became an eighty-five percent drop-out rate among American high school students.

Good jobs were harder than ever to find, unless a person wanted to work in the outer space business. You had to hand it to the Chinese. Oh, I know a lot of people in my neck of the woods were mighty pissed when Dung Myk-Jung decided to make a bid on the U.S. China United States United States California

Lord, those jobs did come. Anyone with at least a tenth grade education who could pass an easy physical examination was eligible for a job in space work. According to the Circleville Herald of June 1, 2024, twenty-nine million five hundred thousand Americans held jobs in the private sector of space travel. Of course, not each and every one of those men and women actually got off the ground. Lots of them worked behind the scenes in button pushing and knob polishing capacities. Not only that, but stories trickled in once in a while about really bad working conditions out there on unregulated Jupiter. But better than one in one hundred of the people willing to work for NASA found out what it was like to leave Earth’s atmosphere. The Chinese Fascist government recruited a German administrator name of Ernest Eichmann to be the head of NASA. Eichmann was wildly popular out here in the rurals for his anti-immigration hiring policy. His first rule was that if an applicant didn’t have at least three preceding generations of natural born citizenship, that person was informed not to waste his time in the job line at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Having been on the raw end of discrimination myself, I wasn’t particularly thrilled with that policy but, as usual, I was in the minority.

Naturally there would never have been such a demand for labor had it not been for the discovery of fuel on Jupiter. Once again, those Chinese were a few steps ahead of us. It turned out that all those swirling gases, all that hydrogen and helium that had obscured astronomers’ views of the largest planet for millennia, well, it turned out those gases were masking an actual repository of Vludium deep down in the planet’s core. Vludium was the newly discovered wonder fuel that was revolutionizing the way Earthlings powered their cars, planes, homes and gardens. Already one in nine new cars manufactured in Atlanta , Georgia Ohio

All the same, I have to confess that I was a little skeptical about the Chinese takeover. I mean, any kind of big change like that is bound to leave an old timer such as myself a bit weary. One thing I did know: smart as he was, nothing in the book Yogi Berra had written was going to help me figure out what Henry had put in those eggs, much less what it had done to me. That being said, I did what any other eighty-eight year-old man in my condition would do. I broke into the restaurant.

I don’t want to make it sound like that big of an operation on my part. Truth is, it wasn’t all that hard. After all, I did have a key to the place. Still, I waited until long after dark, holding a flashlight in one hand and my cane in the other. I didn’t really need the cane, but my thinking was that if I got caught, a cane might be good for the sympathy vote. For that matter, I had a couple explanations planned, just in case I needed them. The first idea I came up with was that, before he died, Henry had asked me to stop by a couple times that night just to make sure the joint wasn’t getting burglarized. In the event that I couldn’t get that set of words out of my mouth, I could always tell the deputy or the Sheriff himself that I’d forgotten to lock up earlier and raced over to Lucado’s to tend to that detail when all at once I realized I needed to use the restroom. Or I suppose I could have just told them I was looting the place. It probably wouldn’t have mattered.

As it happened, none of those contingencies was necessary. The key worked just fine and my Chinese-manufactured Lite ‘n’ Dark Infrared Flashlight lit up the inside of the restaurant mighty nice. Chances are the law enforcement folks were busy breaking up local small-time radical organizations that had sprung up in response to the formation of the New United States. There were some folks on both the left and the right who didn’t like the new way and they kept Radcliffe and his boys busy. Even without worrying about that, I still felt jangly. There is something inherently creepy about walking through a closed-up greasy spoon at three in the morning, especially when you got no legitimate business being there. I’d left the chairs all upside down on top of the tables and I’d wiped down all the booths. Not a note of music piped out of Henry’s ratty old speakers. The taste of disinfectant hung in the air thick enough to kill the most treacherous bacteria. All those observations coalesced in my thinking and it struck me that it’s kind of curious how when you’re in a place that’s dark, even if you know the place as well as I did Lucado’s, you still move slow so you avoid cracking your knee on the edge of something that an idiot repositioned even if that idiot is yourself. I swung my flashlight across the dining room and found it deserted, true to form. I hooked my cane in my belt loop and tread back through Henry’s kitchen and into his pantry. Henry had been a big one for labeling things. He had a section marked for seasonings, spices, toppings, tenderizers, garnishes, fillers, and additives, but not one blessed thing saying “Special powers to use in the event the world goes nuts.”

I tried to remember what was so special about the taste of those fine scrambled eggs he’d served me. I knew how he normally made them. Beat two eggs into a mixing bowl with a fork, plop in half a cup of milk, pour it on the grill and dabble in a tablespoon of cottage cheese and chives. Sometimes he’d spruce it up with a pinch of garlic or maybe he’d go wild and sprinkle in some blue cheese. But God knew he wasn’t gonna spare the chives. Practically everything Henry ever cooked had chives in it, except possibly his apple pie, and even with that there was no way to be sure. Funny bugger that he was, he had chives in every one of his marked-off sections. I guess he figured they were good for seasoning, tenderizing and garnishing all at the same time. But those eggs: they had had an unusually sweet taste, something that wasn’t quite sugar or honey and wasn’t enough like cinnamon to be related to that. It didn’t have enough tang to be paprika or cayenne pepper. What the blazes could it have been?

I closed the pantry door and turned to head back to the kitchen when the tip of my cane got caught on the flap of a box of produce sitting next to a chopping table. It didn’t make any kind of logical sense to check, but there are those who still swear by divining rods, so I figured if my cane had more sense than I did, the least I could do would be to check and see what was in that box.

Red bell peppers. I held one up to my nose and knew for sure. Something I’d forgotten came back to me just that fast: I had seen little pieces of something red in the scrambled eggs and hadn’t given them the slightest thought. Everything Henry made always hit the spot, so I’d gotten out of the habit of even thinking about questioning his recipes. A guy gets hungry, he goes to a restaurant, orders food, gets it brought to him, eats it, pays for it, and doesn’t even slow down to think about how much better he feels. Red bell peppers were no stranger than anything else Henry might slip into his eggs, just to see how it went over.

Red bell peppers. I’d seen those things my whole life, of course. But there was something very odd about this one. It had a faint glow, even in the dark. Its feel was different, too, kind of like holding a ball of slime that had hardened over. And something inside it seemed almost alive, shivering to get out. Henry, what the hell did you have here?

I shoved the pepper into my shirt pocket and hoisted the rest of the carton up on my shoulder, leaving Lucado’s otherwise just the way I’d found it, tossing the fruits in the trunk of my Challenger and returning to lock the place back up.

Red bell peppers. How many times had I eaten such things over the years? One hundred? One thousand? Ten thousand? I’d always loved the taste. It never once crossed my mind that there might be something extra special about them. Or that years of eating the sweet things might actually have meant something.

Back at my house I put my ill-gotten goodies in the refrigerator and scurried over to the gardening section of my home library where I finally settled on Jasper Hedges’ definitive Fruits You Thought Were Something Else. Deep in the book I read that bell peppers, which the people around my neck of the woods had often referred to as “mangoes,” had been around for better than 5,000 years, originating in South and Central America . Matter of fact, it was Chris Columbus himself who brought a big bag of seeds back to Spain with him, thereby introducing what he mistook for traditional pepper to the Eurasian continent. One of the things that set bells apart from the spicy type of pepper was the showing in the bells of what they call a recessive gene that killed off something called capsicum, the stuff that gives regular peppers their flame. Jasper Hedges listed all the known nutrients and the ones that jumped out were Vitamins A and C (neither of which had been shown to let a person change old women into young ones or shatter windows just by force of will, and my apologies to Linus Pauling), lycopine, zeaxanthin, and something called xanthophylls, also known as beta-cryptoxanthin. This last nutrient had been scientifically proven to enhance eyesight in cataract sufferers and also looked to be promising in warding off lung cancer in heavy smokers. Beyond that, there was little encouraging data and I was getting ready to bail on the whole idea when I unstuck a pair of pages and saw that there was a word or two mentioned about pre-Columbian uses of red bells. I now quote from page 122 of Hedges’ manuscript:

Indian tribes along the mountainous borders of Brazil and Uruguay

I didn’t know for sure what I knew, but I did know I was on the right track.

The problem was that lots of people ate red bell peppers every day and so far as I could tell not a one of them grew any special powers the way I had. I wondered if you had to mix them with some of Henry’s chives, but that didn’t make any particular sense. Somehow he had gotten hold of a very special variety of sweet pepper.

The box the bells came in was marked Marybeth’s Fresh Fruits. The address in letters so tiny I had to put on my reading glasses was local, a whole foods farm just off Lancaster Pike. I copied the address in my little notebook and decided to visit this Marybeth individual the very next day.

Chapter Three

Back when Bert Kerns and Henry Lucado and I were all kids together, say maybe around the age of seven or eight, back when I still had to concentrate so that I didn’t click too much when I talked, one of us, probably Henry, started spreading the idea that there was such a thing as magic food. It was a curious idea, that one was, that if a person ate a lot of certain foods, he or she would not only be stronger than the average bear, but might even just possibly if he played his cards right and didn’t get run down by a train just go right on and live forever. Being kids, Bert and I suggested that the magic foods were things like ice cream and candy bars, but Henry, being even at that age more culinary-minded than the rest of us, he shook his head and spat and told us no, it wasn’t sugary things that would keep us alive but instead foods he happened to like. He convinced us that radishes, for example, if eaten in the proper quantities, added some ingredient to the bloodstream that would fight off any disease known to mankind. Likewise, raw yellow onionskins, if flash fried in natural butter, was guaranteed to so improve a guy’s memory that pretty soon he’d be able to recollect details from the day he was born. And green olives, sans pimento, if eaten by the handful every day, would make a boy wildly attractive to the opposite sex, while presumably doing something similar for young ladies. Henry was also big on garlic and vinegar as foods that would ward off infection, and, truth be told, until that last day of May when Bert came up to me outside Elroy’s Sunoco station, I never knew either one of those fellows to be sick a day in their lives. Eighty-eight years old and neither one ever missed a day of work, ever missed a day of school, ever missed out on anything that I’d heard about. As for myself, I was a bit less of the fanatic about my diet. When the three of us had talked about magic foods, I’d thought of it as just a kid’s game and nothing more. All the same, I did like my fruits and vegetables right along with my can after can of Circle-Cola.

It was true. I’d have a can with breakfast, a can with lunch, two cans with dinner, plus I’d sneak in a couple more here and there so that by day’s end I had gulped down at least a six pack and sometimes a little bit more. Around town, everybody more or less joked about how much of the stuff I drank, but at the same time it seemed to distract them all from the occasional click sound I made when I was feeling stressed out. Now I’ll be the first to admit that such a heavy concentration of caffeine and sugar might account for why I had trouble sleeping nights, but Doc Rocky, he told me, he said, hell, you gotta die of something so it might as well be something you enjoy. But there was more to it than that. There was a lot more. Right after the first of the twentieth century, Circle-Cola and a few other of those things that we nowadays refer to as soda pop, they were marketed as remedies for what ailed you. Naturally, when people said, hey, I wonder what it is that’s so good for you in a soft drink, it turned out that the amphetamine in Circle-Cola tended to give a fellow a bit of a lift, but that by and large it was nothing more or less than the carbonated water that made people so convinced that what they were drinking was a real health treat. After a few decades passed by, the head honchos at Circle-Cola started concentrating all their energies on manufacturing the “product” or “formula,” which was just in-house terms for the solid material that the bottlers added actual carbonated soda water to in order to make the real elixir. And that formula was a well guarded secret for a lot of years. Some wise acres used to taunt me by saying that I couldn’t tell the difference among Circle-Cola and Pepsi and Royal Crown and Coca-Cola, but those smart alecks was full of something other than cola beans, because I would set up my own blindfold test and show them wrong every time.

Well, the long and the short of it is that Circle-Cola, or Double C as we sometimes called it, was a mighty popular drink in the central Ohio area for better than a hundred years, Coke and Pepsi and all those other boys never quite making it the poor man’s beverage they’d hoped it would become. Marybeth Gawon had worked at the Circle-Cola plant right there just outside of town for better than forty years before she retired to a life of raising her own popular brand of organic fruits and vegetables.

I dropped by Marybeth Gowan’s farm that next morning to do a little friendly inquiring. From the looks of things, I took Mrs. Gawon to be somewhere near her late sixties, but when I pulled up in my Dodge Challenger, before I could even get out and shut my door I heard her bellowing at her helpers with the force of a woman half that age. “Claude, you lazy miscreant! You haven’t got sense enough to pound sand in a rat hole! Take that bushel of carrots to the back of the pick-up and get on down the road! I hope you don’t think they’re going to drive themselves! Larry, you brain damaged fruit loop! That’s a hoe you’re holding, not a shovel! Lord in heaven, it’s a wonder I haven’t gone broke with lunk heads like you boys working here! Hop to it! Chop-chop!”

Her two field hands just grinned and nodded and kept on about their business, tipping their hats as I walked by them to extend my shaking hand to Marybeth Gawon. “Morning, ma’am,” I said, removing my own hat and waiting for her to dust off her hand before slapping it firm into my own.

“Maurice Washington, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Mrs. Gawon. How are you this fine day?”

“Little busy trying to keep those idiots from driving me to the poorhouse. Never too busy to set a spell and chew with an old friend, though. Take yourself a seat, Mr. Washington

Once she made to do the same I straightened out an old sun-battered lounge chair and tried to lean forward in it. “How’s the crops this season, ma’am?”

She took a pair of small silver-framed lenses out of her apron pocket, polished them on the hem of her dress and perched them on her nose, regarding me over their tops. Looking back at her, I got the idea that she’d heard every line of bullshit ever uttered and had spread some of it herself as needed. “Just fine, thank you,” she said. “I expect this to be a record season in organics. People’s sick and tired of gnawing on that wormwood that passes itself off for food these days. Genetically modified pig slop. Here, taste this apple.” She plucked a red delicious out of her smock pocket and fired it to me like a pitcher throwing to first base. I caught it barehanded and sunk my teeth into it.

“Bet you haven’t tasted one that perky and sweet in thirty years, eh?”

She was right. Biting into that apple was like somebody had placed a cold washcloth over my face. I had been so tired from lack of sleep that I was struggling to keep my thoughts straight. I took a couple bites of that apple of hers, grown in her orchard about half a mile back off the main road, and daggone if I didn’t feel more clearheaded right off.

“It’s very good, Mrs. Gawon,” I said, trying hard not to click. “Funny enough, that’s kind of why I stopped by today. You grow bell peppers here, don’t you?”

She tipped her head back and looked at me right through her tiny glasses. “I do. Been raising bells since back in the days when some fools called them mangoes.”

“I had one of your red bell peppers the other day. It was—amazing.”

Now she was the one leaning forward. “They turn red if you leave them on the vine long enough. That’s when they’re at their peak. I’m delighted you enjoyed it. How do you know it was one of mine?”

“It was in my scrambled eggs. I eat most mornings at Lucado’s.”

Her lips formed a straight line. “Henry Lucado? One of my best customers. Always paid on time and never bitched about an order. Tragedy.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Who’s going to tend his restaurant now?”

She was a smart old bird. I had to give her that. “I really don’t know, ma’am. His kids have all moved away. Arizona

She looked at me until my cheeks grew warm. I blinked and she stood and motioned me to my feet. “Let’s go for a walk,” she said. I walked alongside her back around behind her barn, past a pair of silos and a couple of sheds. The smell out here was a fine blend of fruits, vegetables and animal excrement. Anyway, I hoped it was from animals. At last we entered a small building with a purple ring and triangle in the middle hanging up over the entrance. She uncorked the lock on the door, dropped the key back in her smock, and opened the door just wide enough for the two of us to enter if we inhaled and didn’t swallow on the way through.

Sitting on our right were some fat cylinders wrapped in the kind of paper that grocery bags used to be made out of. A strand of thin rope wrapped around in a cross shape secured each cylinder from invaders. Straight ahead was block after block of what my nose told me was horse dung. It was compressed and shoved into squares about the size of a brick you might use to build a house, that is, if you had a couple thousand of them and didn’t mind the odor. The stench was difficult not to notice. And then to our left sat what had to be at least two dozen shelves, upon each of which was a long row of small clay pots.

“Do you like to watch what you eat, Mr. Washington

“Not that much, ma’am. I like to taste what I eat.”

“Let’s not be glib, sir.” She turned to face me. Even though I stood nearly a foot taller, I somehow sensed that she was looking down at me. She said, “Henry served you one of my red bells, didn’t he?”

“I believe he did, yes.”

“He must have considered you to be an honest and decent man.”

“Well, he didn’t make his intentions especially clear to me.”

She nodded as if internally debating whether to swat a fly or save the universe. “Him serving you one of my red bells speaks for itself. He wasn’t an idiot, would you say?”

“Certainly not.”

“He didn’t appear to be inebriated at the time, did he?”

“He did not.”

“No Chinese soldiers with knives to his throat?”

“I didn’t see any.”

“Fine. Then he selected you.” She appraised my appearance. “I would take you to be in your late seventies?”

“I’m eighty-eight as of last month.”

She drew back a step. “Eighty-eight. Same as Henry. Same as another recently deceased young fellow, Bertram Kerns. You all must have grown up together. But you were the only one with the click, weren’t you?”

I felt my cheeks getting warm again. “What do you mean by ‘the click’?”

She stirred at the dirt with one shoe and finally looked me back in the eye. “Where are your people from, Maurice?”

I was getting uncomfortable and decided to change the subject. “What do you mean he selected me?”

She walked around me as if inspecting a steer someone was thinking of hiring out to stud. “Yes, he selected you. Mr. Washington

“I would call myself a socially confused individual.”

She smiled in spite of herself. “I see. Perhaps I can clear up some things for you. But first, I am curious. Have you had any feelings or sensations since your meal at Lucado’s? Have you noticed anything different about yourself?”

I nodded. I was afraid that if I opened my mouth that all my brains would come spilling out.

She continued. “Yes, you certainly have, haven’t you? How is your general health, Mr. Washington

“You can call me Moe, ma’am. Most everybody does. My health has been pretty good, I suppose. I mean, I get the occasional ache and pain. Rheumatoid arthritis in my back and shoulders from time to time, that’s about the worst of it.”

“And how is your discomfort today, Maurice?”

I thought about that. Another shiver went through me as if a goose had just walked over my grave. I hadn’t had so much as a twinge of pain in two days, not since right after my breakfast at Henry’s. But I didn’t answer her question. She didn’t seem to need me to do so.

She said, “Do you know anything about genetically modified foods, Maurice?” I did know a little about them, yet before I could answer she went on. “No, I don’t suppose you would. Here’s a quick lesson for you. Back as far as the early 1970s, big agricultural conglomerates started messing around with the food that people ate. They started radiating seeds, started figuring how to get more produce out of smaller and smaller tracts of land. Pesticides not only killed off the bugs that plague any farmer, they managed to grow two stalks of corn where only one had grown before. If you take the gene out of this seed and grow it with the gene of this other seed, you’d get a super seed that would grow more food in less space. Sounds ideal, doesn’t it? It most certainly was not ideal. It was a disaster. What ended up happening was that the taste eventually went out of most of the foods and along with the taste went the nutrients. But by golly, there was plenty of food raised. Food could be bought by poor countries and starving kids and mothers could be fed where before you’d have just had mass starvation. Nobody much cared that the fruits didn’t have one-tenth the vitamin levels they’d had before, and as for the taste, well, hell, when you’re hungry, taste doesn’t matter as much as getting full. Never mind that the fat content of these foods was so high that the person eating them couldn’t ever quite eat enough to feel satisfied. Remember when you were a boy, Maurice, and you’d slice open a nice fresh watermelon and sit there and eat the whole thing and you’d be so full of juices and sugars that you thought you’d never be able to take another bite as long as you lived? It looked like days such as those were gone forever. But that turned out to be incorrect. You see, there are a few smart folks out there. I was one of them. I had a plan. And I made it work.”

She was rolling now. I could see the wide forehead clear itself of wrinkles as she motioned first to the cylinders, then to the dung bricks, and finally to the clay pots. “I am a smart woman, Maurice. There’s no reason to hide my candle beneath a basket, as the Lord says. No reason indeed. Things are mighty strange in the world right now, wouldn’t you say? I would be very interested in knowing how my pepper affected you, Maurice.”

I told her about Margaret Maxwell. I told her about the window glass in Tiny Mitchell’s office. I even told her about thinking that maybe I could have helped Bert Kerns but had been too chicken to do so. With each detail she squinted at me more closely. At last she took another step back. “Maurice Washington, I am going to trust you, just as our friend Henry trusted you. I tried out my first batch of red bells on Claude and Larry two summers ago. It made them into work horses for several weeks, although it didn’t do much in terms of smartening them up any, as you can probably tell. Trial and error, repeat ad nauseam, and late this spring I came up with a combination of processes that looked promising. Now with your visit here, I suspect that these days in which we live are not merely strange but interesting times. Let me show you something.”

I never was much of a science buff, but the gist of the thing was that she soaked her bell seeds for about a week in a mix of apple cider vinegar grown from apples on her own trees. Then, before planting, she plotted about a dozen of them in a brick of horse manure. All this, she assured me, only came after she had experimented with different strains of pepper seeds. She had worked over a microscope for months, burning out what she called the impurities until she felt satisfied and started the growing process. The vines had shot up fast and the fruits had hung heavy. She had eaten several of the peppers herself and, despite finding the taste richly satisfying, hadn’t noticed any particular change in her own physiology. According to Mrs. Gawon, there was a racial component to the make-up of the person eating the fruit that affected the individual reaction. “I would wager,” she said, “that you can trace your genetic heritage back to the Bushmen of Namibia. I mean, it’s common knowledge that everyone can, to some degree. Spencer Wells and half a dozen other scientists have demonstrated this. But in your case, just based on your manner of pronouncing certain words, I would guess that your lineage is perhaps more direct than that of many other people. What do you know about your ancestry?”

“From what I’ve been able to learn, my great-great-great grandmother came from Africa . Not of her own free will, if you take my meaning.”

“Go on. Go ahead.”

I knew my history better than most. I knew it well. “The language my ancestors spoke is called Taa. It’s the tongue spoken even today in southern Khoisan. Most of the 2,000 or so people who still use it live in Los Angeles Namibia and Angola

“This is amazing. Do you realize, Mr. Washington

I supposed we were beyond the point of modesty, so I unbuttoned my shirt and pulled at both collars, displaying my very own newly grown purple circle with interior triangle, a smaller version of the logo above this barn. It stood out about a quarter inch from the rest of my skin.

She moved very close to me. “Yes, see how pronounced the coloring is? Surely it is. It’s likely harmless. It may not even be connected to the plant at all. But what if the accidentally created genes in my red bell peppers triggers something in your system and does it because of your connection with the very first people? I suppose I’m speculating too much.”

I smiled. “I don’t know, Mrs. Gowan. Marybeth. I don’t know. I guess it is possible.” Things were spinning in my mind like cats in a mouse house.

She continued. “My guess is that whatever it is that birthed that marking on you interacted with my special bells and gave you your new abilities. You saw that same symbol on the barn out front? That came from me. I should say it came from a sort of dream I had. It wasn’t quite a dream, though. Whatever it was, I had that symbol in my mind and I didn’t even know why but I had a strong yearning to paint that symbol on this barn. Peculiar, I know. Have you had that young quack Seitz examine you?”

I told her I had not. “He’s not really a quack,” I put in. “Matter of fact—”

“It’s just as well. Still, I’d love to take an epidermis sample, if you have no objections. We can do that before you leave today.” She was in her own head now. She stared at me and I could tell she wasn’t really seeing me any longer. I took a step back and was trying to think of a gracious way to get out of there. Then she said, “I’d be fascinated to see your power in action.”