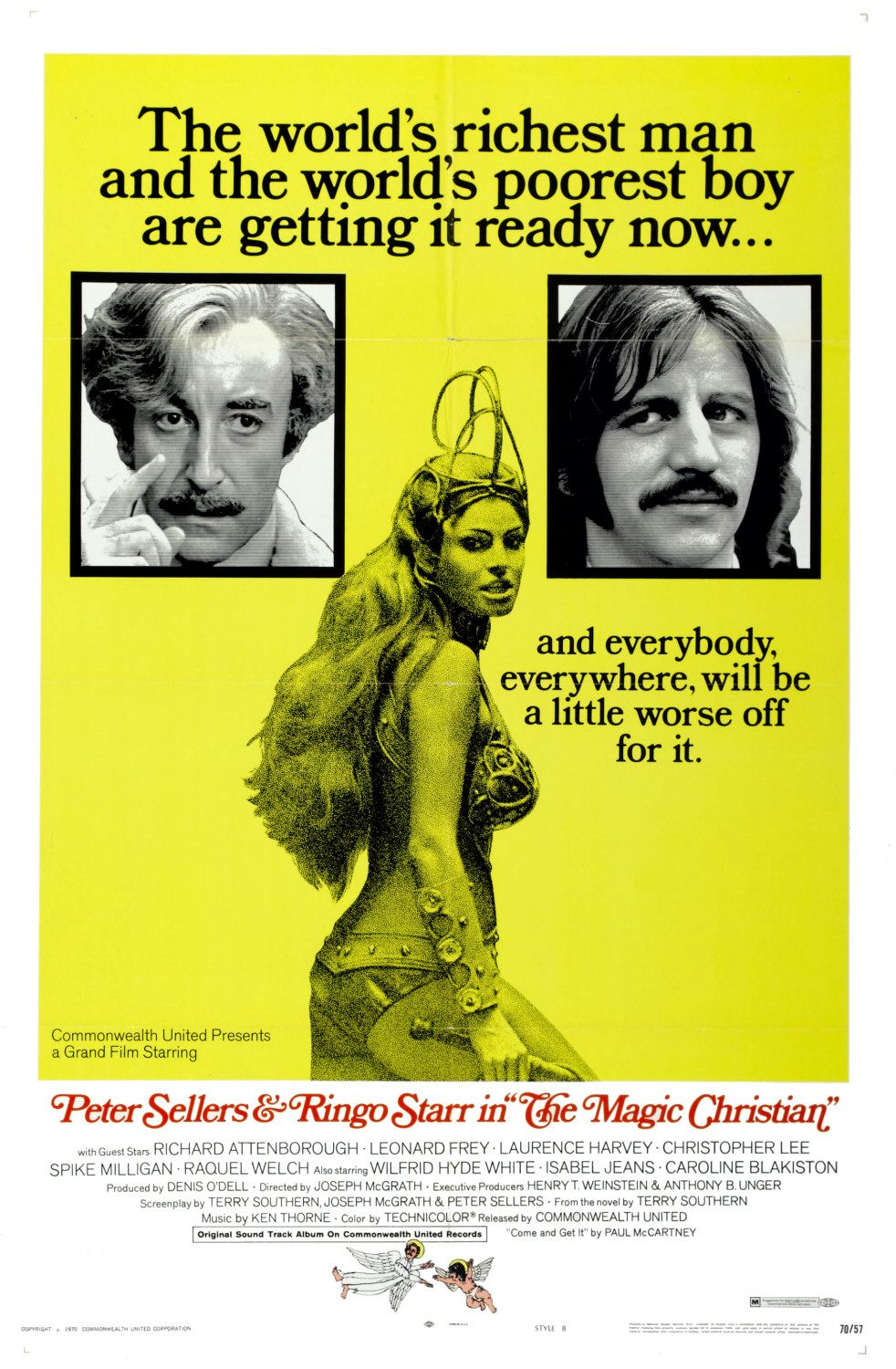

Because I never cared for the films of Blake Edwards (too obvious and far too pro status quo for my tastes), I never got around to enjoying the Pink Panther movies and as a consequence I dismissed a lot of the work of Peter Sellers. That does not mean that I lacked appreciation for the actor's best works, such as Dr. Strangelove and Being There. What it does mean is that I often questioned Mr. Sellers' judgment. That's all. So when it came time for me to reevaluate the film The Magic Christian, I didn't know quite what to think. On the one hand, starring Sellers and Ringo Starr, with cameos by Raquel Welsh, Roman Polanski, and Richard Attenborough, with a script by the brilliant satirist Terry Southern, with contributions by some of the guys who would soon become Monty Python, and with a soundtrack by Badfinger,the bloody thing could hardly seem to miss. And yet for some reason I recollected not caring much for it when I first saw it as a wee bit of a lad upon its initial release way back in December 1969.

Rest assured, my cocoon worshipers and friends of many-colored nomads, time has only improved the quality of the humor which constructs The Magic Christian, a film with the revealing tagline "The Magic Christian is: antiestablishmentarian, antibellum, antitrust, antiseptic, antibiotic, antisocial & antipasto."

The storyline really doesn't matter all that much, as you may have guessed. The premise, however, is that Guy Grand, played by Sellers, asserts that anyone can be bought for a price. Okay. Money sucks, especially if you've a lot of it and have the safe perspective of being insulated. But, wait! Isn't that Ringo playing a bum sleeping in the grass? Why, yes, I believe it is, and that suggests that the Beatles drummer really was, as everyone said in those days, the best actor of the bunch. He actually was a mighty fine study of a fellow, and no one should ever take that accomplishment away from him, other than to add that despite Caveman, Ringo actually is a first rate thespian in his own right and needn't be compared to other musicians for his credentials.

The only reason to watch the 92-minute feature film these days, it stands to argue, is that Starr and Sellers work so well together that it is almost possible to believe that the two real life hipsters were indeed related, if not to one another, then to someone, for certain. The actual skits that loosely construct the film haven't aged particularly well, and the plot, as I say, is a tired one now, as it was forty-odd years back, although fans of Python will probably find something there to amuse themselves and rightly so.

Aside from the comedic brilliance of the two main stars, the other reason to lap up this film like milk on a doorstep (if one were a cat, that is) is because of the truth of the tagline. I can't speak to the anti-pasta sentiments, but it certainly was and remains everything else on that list of words and even to this very day in this very new year resounds with disrespect for the stalest elements of the pablum and pap that the 1970s would stomp the guts out of, such as the nauseating mainstream musicals, of which My Fair Lady was perhaps the most abominable example. The perversity of mediocrity and their merchants did not die easily, of course, and so we would soon enough find ourselves swallowed up in the reactionary swill of Jesus Christ Superstar, Hair, Grease and all the other spoiled cream that the squares imagined the 1960s were really about. The Magic Christian is simply a fish slammed against the face of people leaving the theatre asking (as many did when presented with genuine brilliance, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey), "What the bleeding hell is this movie about?" The very framework of a motion picture having a beginning, middle and end, in the Aristotelian sense of plot and progress, was one which movie-makers did not presume to universally accept. You could not make The Magic Christian today any more than you could make 2001, specifically because Guy Grand was correct: people do have their price and can be seduced into selling out. That, it seems, is the precise reason why I hope that someone will try.

Rest assured, my cocoon worshipers and friends of many-colored nomads, time has only improved the quality of the humor which constructs The Magic Christian, a film with the revealing tagline "The Magic Christian is: antiestablishmentarian, antibellum, antitrust, antiseptic, antibiotic, antisocial & antipasto."

The storyline really doesn't matter all that much, as you may have guessed. The premise, however, is that Guy Grand, played by Sellers, asserts that anyone can be bought for a price. Okay. Money sucks, especially if you've a lot of it and have the safe perspective of being insulated. But, wait! Isn't that Ringo playing a bum sleeping in the grass? Why, yes, I believe it is, and that suggests that the Beatles drummer really was, as everyone said in those days, the best actor of the bunch. He actually was a mighty fine study of a fellow, and no one should ever take that accomplishment away from him, other than to add that despite Caveman, Ringo actually is a first rate thespian in his own right and needn't be compared to other musicians for his credentials.

The only reason to watch the 92-minute feature film these days, it stands to argue, is that Starr and Sellers work so well together that it is almost possible to believe that the two real life hipsters were indeed related, if not to one another, then to someone, for certain. The actual skits that loosely construct the film haven't aged particularly well, and the plot, as I say, is a tired one now, as it was forty-odd years back, although fans of Python will probably find something there to amuse themselves and rightly so.

Aside from the comedic brilliance of the two main stars, the other reason to lap up this film like milk on a doorstep (if one were a cat, that is) is because of the truth of the tagline. I can't speak to the anti-pasta sentiments, but it certainly was and remains everything else on that list of words and even to this very day in this very new year resounds with disrespect for the stalest elements of the pablum and pap that the 1970s would stomp the guts out of, such as the nauseating mainstream musicals, of which My Fair Lady was perhaps the most abominable example. The perversity of mediocrity and their merchants did not die easily, of course, and so we would soon enough find ourselves swallowed up in the reactionary swill of Jesus Christ Superstar, Hair, Grease and all the other spoiled cream that the squares imagined the 1960s were really about. The Magic Christian is simply a fish slammed against the face of people leaving the theatre asking (as many did when presented with genuine brilliance, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey), "What the bleeding hell is this movie about?" The very framework of a motion picture having a beginning, middle and end, in the Aristotelian sense of plot and progress, was one which movie-makers did not presume to universally accept. You could not make The Magic Christian today any more than you could make 2001, specifically because Guy Grand was correct: people do have their price and can be seduced into selling out. That, it seems, is the precise reason why I hope that someone will try.

The estimable William Friedkin directed and Mart Crowley wrote the screenplay for The Boys in the Band, the first overtly gay film with a budget in the seven figures. The film starts out funny and uncomfortable, just like the party it is superficially staged around. The plot turns bitter once a nasty telephone game is introduced to the birthday shenanigans and honesty gets put on the chopping block. Anyone threatened by the campy artifice enacted by some gay men will become positively apoplectic from watching these wild characters and other viewers may find themselves just as jarred as the character Michael is when the party is punctuated by the presumably straight Alan, a friend from college. The dialogue, or the chatter, or the bright badinage, is often brilliant and anyone who cringes just because of the sexual orientation of the people in the film is denying himself/herself one hell of a good ride through the uncanny realism of a culture that has not changed all that much since its release in 1970.

And that's pretty interesting because, as with the previous film--The Magic Christian--and for a completely different set of reasons, this film wouldn't stand much of a chance of being made today, although people would love it if it were. You see, the film is smart, something which is not true of all Friedkin product, the credit for which going to screenwriter Crowley. No, you couldn't make this film now because of studio fear that people wouldn't want to see it or that psycho-zealots would boycott or from their own terror at the prospects of being linked to such a film. This film in fact is so gay that most religious zealots would refuse to boycott it just because they would fear being linked, if only in opposition. This is not La Cage aux Folles. This is an angry movie that uses humor as a whip.

The only problem with the film or the off Broadway play from which the entire cast was drawn is in the self-deprecating nature of the dialogue. When I was in college, a lot of my friends were gay, or said they were gay, or wished they were gay, and so I found myself at the occasional party when I was one of very few straights and was often treated as if I fit in, which was actually a compliment to me, so I didn't mind. Well, one thing and another and alcohol would pour and people would become more loose in their speech and I would hear people referring to themselves or to one another as bitch, faggot, queen, and the like. At first I was surprised to hear lines like "Oh, you've had worse things than that in your mouth," delivered from one man to another. Hell, you get used to it, I suppose, just as I did when I was hanging out with African-Americans who referred to themselves and one another in similarly disparaging manners. In The Boys in the Band, the sub-dermal self-loathing (masquerading as parody of straight stereotypes but a little too close and constant for that to be all it is) balls its fists and punches you repeatedly in the stomach, over and over, as if to say, "Hey! You get it? I'm pissed!"

We get it, we get it, take it easy, everything's okay.

Everything, that is, until you read the Facebook entry of a cretinous friend of a friend of mine who taunts the posthumous life of one of the teenage boys who offed himself rather than endure the constant tortures and taunts of his presumably post-enlightened classmates. I strongly considered giving up this imbecile's name just so anyone so inclined could ring him up and give back a little of what he and his slithering ilk dish out, but then I realized that anyone undeveloped enough to think that saying "Splash!" somehow negates an opponent's argument isn't worth the trouble. I will, however, suggest that you watch this film on YouTube and then consider ordering a copy that you can send to your most despicably bigoted colleague. Think of it as film as guerrilla warfare, something sorely missed in modern cinema.

And that's pretty interesting because, as with the previous film--The Magic Christian--and for a completely different set of reasons, this film wouldn't stand much of a chance of being made today, although people would love it if it were. You see, the film is smart, something which is not true of all Friedkin product, the credit for which going to screenwriter Crowley. No, you couldn't make this film now because of studio fear that people wouldn't want to see it or that psycho-zealots would boycott or from their own terror at the prospects of being linked to such a film. This film in fact is so gay that most religious zealots would refuse to boycott it just because they would fear being linked, if only in opposition. This is not La Cage aux Folles. This is an angry movie that uses humor as a whip.

The only problem with the film or the off Broadway play from which the entire cast was drawn is in the self-deprecating nature of the dialogue. When I was in college, a lot of my friends were gay, or said they were gay, or wished they were gay, and so I found myself at the occasional party when I was one of very few straights and was often treated as if I fit in, which was actually a compliment to me, so I didn't mind. Well, one thing and another and alcohol would pour and people would become more loose in their speech and I would hear people referring to themselves or to one another as bitch, faggot, queen, and the like. At first I was surprised to hear lines like "Oh, you've had worse things than that in your mouth," delivered from one man to another. Hell, you get used to it, I suppose, just as I did when I was hanging out with African-Americans who referred to themselves and one another in similarly disparaging manners. In The Boys in the Band, the sub-dermal self-loathing (masquerading as parody of straight stereotypes but a little too close and constant for that to be all it is) balls its fists and punches you repeatedly in the stomach, over and over, as if to say, "Hey! You get it? I'm pissed!"

We get it, we get it, take it easy, everything's okay.

Everything, that is, until you read the Facebook entry of a cretinous friend of a friend of mine who taunts the posthumous life of one of the teenage boys who offed himself rather than endure the constant tortures and taunts of his presumably post-enlightened classmates. I strongly considered giving up this imbecile's name just so anyone so inclined could ring him up and give back a little of what he and his slithering ilk dish out, but then I realized that anyone undeveloped enough to think that saying "Splash!" somehow negates an opponent's argument isn't worth the trouble. I will, however, suggest that you watch this film on YouTube and then consider ordering a copy that you can send to your most despicably bigoted colleague. Think of it as film as guerrilla warfare, something sorely missed in modern cinema.

It is not overstating the matter when discussing the attributes of The Ballad of Cable Hogue to argue that with the understated talents of lead Jason Robards and visual stunner Stella Stevens, this film, while something of an artistic failure, is among the most ambitious and heartwarming failures in the western genre. In fact, I like to think that the best aspects of this charming film are Robards/Hogue's internal struggle between revenge and the more Christian aspects of his personality; the cosmic beauty of Stevens as Hildy, a woman whose body itself is every bit as fascinating as the western skies; the blowing away of the lizard in the opening moments (which is the only truly violent scene in the film); and the introduction of the horseless carriages near the end of the film, cars which look so strange when rolling across the cheap and eager landscape. All of those elements are important to the fun of the film, but Peckinpah refused to have his movie be just another period piece that made subtle commentary of the transformation from horses to automobiles. He insured the longevity of his film with cinematic techniques rarely if ever seen in the western film: super-imposing of close-ups over wide screen shots, double split screen images, the use of the human body as landscape, fast motion sequences. These and other techniques were becoming virtually de riguer in motion pictures by 1970. But no one had applied them to the horse opera and certainly not to the morality tale horse opera.

The songs that bookend and punctuate the movie weren't much to begin with and they have aged like spoiled eggs. But that's the worst thing one can say about this film. It may not have inspired anyone--except possibly Sergio Leone, who by this point had already recognized what a terrific talent Jason Robards was from Once Upon a Time in the West. Those it did inspire sat in the movie houses with their mouths agape at the success of the bum prospector and the fetching prostitute with a heart of gold.

If my sniveling retelling of the plot reeks of cliche, these elements weren't cliche at the time of the film's release in 1970. The sexism in the movie is real, be forewarned. It is also puerile, stupid and didn't reinforce bad behavior in anyone, except possibly in the retelling of the only line I will ruin by repeating it here. Cable Hogue demands payment to a preacher who keeps popping up in the movie. The payment is for dinner. Protesting, Hildy the hooker tells Hogue that he never charged her for dinner. Hogue agrees, saying, "That's because you never charged me."

You would have to go back to middle period John Ford work to find a western this appealing to the senses. Art, desert and horses didn't come together in the same movies all that often (Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and possibly Once Upon a Time in the West, depending on who you ask). Unlike Leone and very much like Ford, Peckinpah made his touches of art--at least in this gem of a failure--light as morning desert air. And that's appropriate. After all, if you can taste the air, it ceases to be refreshing.

Stanley Kubrick, for all his genius, did not make movies over the heads of his audience for the simple reason that his films invariably had some character with whom the audience was inclined or coerced into identifying. For all his esoterica, Woody Allen has always been a man of the people, albeit, one with a richer reading list but one who still values the audience response, at least when he does not curl his lips against it, neither approach having the luxury of being supercilious. You could argue that some foreign filmmakers were artful beyond the routine pale, but once again, whether one means Truffaut, Godard, Kurosawa, or Bunuel, the intent to challenge the audience remains a priority over deliberately alienating the paying (or pirating) public.

In order for any film to lay legitimate claim to being beyond the general perception levels, the assertion must be based in a coalescing of the director and writer's imaginations. What the film is about, what happens in it, the motivations of the characters, their dreads and desires, the way the film looks in a darkened theatre, the sounds the audience will scarcely recall yet will have nonetheless experienced, the primordial cave pictures that continue to mesmerize the masses--Dammit, it isn't easy being Robert Altman, as he would be the first to tell you if he hadn't passed away at precisely the proper time.

Brewster McCloud, the film that is the subject of today's analytic dissection, teems and spills over with imagination, from the repetition of the movie's title during the opening credits sequence to the naming names close-out at the end and everywhere in between, this film radiates the power of its creator's mind and since that mind did belong to one Robert Altman then that fact in and of itself should and would be enough to at the very least get our attention if not send half the glee club out to take courses in genuflecting and the odd and occasional curtsy.

But if you balk at enjoying a film solely on the basis of the reputation of its director, the good news of the day is that Brewster McCloud--neglected in its own time--is one of those films about which it is infinitely appropriate to quip, "Mighty fine film, indeed, that one." The cast was pulled from most of the same director's crew on M*A*S*H, minus Gould and Sutherland, meaning that, yes, we do get the sensational Sally Kellerman and yes we do get the unbelievably comic Rene Auberjonois as the bird-man narrator.

Bird-man, do I say? Indeed, I do say. The film is about flying. Whether the vignette pertains to the Stacey Keach character who is a nasty relative of Wilbur and Orville or to sex as a metaphor, flying is the subject and Bud Cort (Boone from M*A*S*H) aims to learn. This is really just a great science fiction film, if you must know, and even though I don't think it was ever recognized as such, the plot could just as easily have come from Philip K. Dick or even Leigh Brackett.

There were probably more stupid movies released in 1970 than any other year to that point in the history of film. There were also more unheralded classics, such as the three we've already peeked at this new year (The Magic Christian, The Boys in the Band, and The Ballad of Cable Hogue, in case you've forgotten). Brewster McCloud (even the character's name works) falls into that category as well. Altman moves the scenes around his characters to the extent that sometimes it appears that the people are standing still and the camera is doing all the acting. Even there this is no accident. Even there this is brilliance at work and woe unto the sad fool who fails to learn to fly right along with the owlish Brewster, a character who fails to draw in the audience, which is probably why the movie tanked on release. People prefer characterization over story-line and technique. I suppose that is proper enough. We should, however, remember that film as a thing, as a craft, is a visual medium and as such it has a responsibility that supersedes the banality of a theatrical plot and rich, subtle characterization. A good film tells a story. A great film brings the audience in and lets them discover the story. This is a great film.

This is the history: The Confession (1970, Costa-Gavras) is the true story of Artur London, a loyal Communist who served with the International Brigade in Spain and with the Communist anti-Nazi underground in France, and who suffered a long term in a Nazi concentration camp. In 1949, Mr. London returned to his native Czechoslovakia from France to become Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the Communist Government of President Klement Gottwald. Two years later, along with thirteen other leading Czech Communists (eleven of whom were Jewish), Mr. London was arrested for treason and espionage and found guilty in what became known as the Slansky trial. This trial, named for the secretary general of the Czech Communist Party, who was also a defendant, was one of the last major wheezes of the Stalinist purges that began with the Moscow trials in the 1930s. All of the Slansky defendants were found guilty and all but three, including Mr. London, were executed. Mr. London lived not only to see the defendants rehabilitated and to write his book but also to return to Czechoslovakia on the day in August, 1968, when Soviet troops invaded his country to end the short Czech spring.

Yep, that is the history. Yet as we see in this beautiful and horrifying film, truth is a lie. Only a lie can set you free. Or so it was in the post-Stalinist trials and purges that swept through the Soviet bloc throughout the years of Khrushchev and his reign of impotence. London, played with such dignity by Yves Montand, is broken down one layer at a time, forced to admit to objective facts while insisting that subjective truths also matter.

Q. You associated with the traitor Smith in 1949?

A. Yes, but I did not know he was a traitor until 1952.

Q. Are you denying that Smith was a traitor?

A. No. I am--

Q. We will deal with the subjective elements later. First, you must memorize your confession. Doctor, bring in the sunlamps. We must prepare this man for trial.

What happened in Czechoslovakia is one of the reasons that some people have abandoned politics altogether. Economics is dependent upon politics for its implementation. Politics is religion and religion is madness. Faith guarantees the freedom of the bull whip. You may go to sleep. What is your number? Louder! Assume the position. Guards! Only your confession can save you. Do you believe what your wife says in this letter? Has this man been bathed in twenty-one months?

The Confession is not Costa-Gavras' most popular film. That would probably be Amen, Missing, or Z, any of which are powerful testaments against authoritarian forces. However, The Confession remains vital in the way it makes no compromise to an uninformed, uninvolved public. One needn't be a student of post-WWII Soviet or Eastern European history in order to get this. One need not have memorized every word of Orwell's novel to find a similarity in the absurd processes used to extract falsehoods that everyone from the interrogators to the members of the tribunal to the general public understood to be falsehoods.

The goal here is not to lead people to a rejection of politics based in apathy. It is rather to tell Artur London's story with some degree of accuracy and to convey the permeating sense of dread that flooded those awful times just as they did, it must be admitted, at other times in our collective history, whether in the days following the attacks of September 11, 2001, or in the days following the revelations of Abu Ghraib. Costa-Gavras does not flinch. The psychologically overlapping flashbacks that let us in on London's "rehabilitation" spoils nothing. On the contrary, the more we learn of his ultimate fate, the more horrified we are at what happens to him in the process of getting there. The colors are bleak, the staging stark, and the acting unbearable in its verisimilitude, or at least its relation to what we are unable to dispute as true. A rose dipped in liquid nitrogen remains a rose, at least right up until it shatters like glass. This film is the liquid nitrogen. Our sensibilities are the rose.

Michelangelo Antonioni made so many outstanding films, it's a pity Zabriskie Point isn't one of them. Before we get too far into this conversation, I should admit that many people love this film and those who do will probably dislike me very much for saying that it dry heaves Saltines. The good news is that as with a lot of movies that don't quite accomplish all to which they aspire, Zabriskie Point is an occasionally enjoyable failure and it still stands heads and eyebrows above the underwhelming majority of stupid love stories popular in that year of 1970, including the most popular turd-licker love story of all time, Love Story.

The first clue that this movie may not be Antonioni's master work is the soundtrack. The opening credits terrified me by announcing music from The Grateful Dead as well as from Pink Floyd, two reasons to leave the theatre if you have anything at all pressing to do. On the other hand, a lot of people find drugged-out hippie music to be exactly what they want after a long day of committing home foreclosures and initiating hostile takeovers, so perhaps I should try to keep an open mind.

I will admit the cinematography is superb, possibly the best aspect (ratio) of the film, especially if you favor fly-along shots of airplanes approaching the top of 1952 Buicks, which I do and so should everyone. The photography is so good that I am not bothered in the least that the movie has no conventional plot. Conventional plots are so. . .well. . . conventional. After all, were it not for the photography in this movie, we would have no choice but to rely on the meager story-line, wherein we find that George cannot be a revolutionary because he is an assassin instead (probably--we never know this for certain), just as mercenaries cannot be fascists. Both assassins and mercenaries work best alone, rendering whatever political persuasion they may favor to be largely beside the point. Because he cannot be a revolutionary, he buys a gun and maybe shoots a police officer. What he does do is steal a small plane and take off after Daria, one of the best reasons to shoplift an airplane that I have ever seen. (In fact, it is the third most popular all-time reason. Number One is: Go to Cuba. Number two is: Leave Cuba. Number three is: Take off after Daria.)

Daria is pretty and George is handsome and politics is so. . .well. . .political. Student activism permeates the first half of Zabriskie Point, to the extent that the discussions in which the globs of young folk engage seem all too real for their inability to persuade. One of the most frustrating aspects of 1960s radicalism was the occasional dip into party ideology and this film misses not one cliche, even if the lines are delivered as tired gospel.

"How you get there depends on where you're at." So reads the movie's theatrical tagline. Whaddya want? Good grammar or good movies? Either one would be fine.

The final uplifting feature of this movie is, ironically, that it is actually about something, whereas so many love stories are about love, which is probably the most uninteresting type of film. Zabriskie Point uses love as a metaphor for flying, and vice versa, what with 1970 being a great year for metaphors of this type, Brewster McCloud using sex in the same exact way, only funnier.

It's up to you. Either you favor Roger Waters and Jerry Garcia making mood music for moderns or you have better things to do, such as thinking. But those airplane shots will still reimburse you for the cost of the DVD or download.

The first clue that this movie may not be Antonioni's master work is the soundtrack. The opening credits terrified me by announcing music from The Grateful Dead as well as from Pink Floyd, two reasons to leave the theatre if you have anything at all pressing to do. On the other hand, a lot of people find drugged-out hippie music to be exactly what they want after a long day of committing home foreclosures and initiating hostile takeovers, so perhaps I should try to keep an open mind.

I will admit the cinematography is superb, possibly the best aspect (ratio) of the film, especially if you favor fly-along shots of airplanes approaching the top of 1952 Buicks, which I do and so should everyone. The photography is so good that I am not bothered in the least that the movie has no conventional plot. Conventional plots are so. . .well. . . conventional. After all, were it not for the photography in this movie, we would have no choice but to rely on the meager story-line, wherein we find that George cannot be a revolutionary because he is an assassin instead (probably--we never know this for certain), just as mercenaries cannot be fascists. Both assassins and mercenaries work best alone, rendering whatever political persuasion they may favor to be largely beside the point. Because he cannot be a revolutionary, he buys a gun and maybe shoots a police officer. What he does do is steal a small plane and take off after Daria, one of the best reasons to shoplift an airplane that I have ever seen. (In fact, it is the third most popular all-time reason. Number One is: Go to Cuba. Number two is: Leave Cuba. Number three is: Take off after Daria.)

Daria is pretty and George is handsome and politics is so. . .well. . .political. Student activism permeates the first half of Zabriskie Point, to the extent that the discussions in which the globs of young folk engage seem all too real for their inability to persuade. One of the most frustrating aspects of 1960s radicalism was the occasional dip into party ideology and this film misses not one cliche, even if the lines are delivered as tired gospel.

"How you get there depends on where you're at." So reads the movie's theatrical tagline. Whaddya want? Good grammar or good movies? Either one would be fine.

The final uplifting feature of this movie is, ironically, that it is actually about something, whereas so many love stories are about love, which is probably the most uninteresting type of film. Zabriskie Point uses love as a metaphor for flying, and vice versa, what with 1970 being a great year for metaphors of this type, Brewster McCloud using sex in the same exact way, only funnier.

It's up to you. Either you favor Roger Waters and Jerry Garcia making mood music for moderns or you have better things to do, such as thinking. But those airplane shots will still reimburse you for the cost of the DVD or download.

The Rolling Stones energized an otherwise druggy and dragging San Francisco night, turning the smell of beer and vomit into a rapturous excuse to forget about the cans of hops that rained down from the sky, courtesy of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club, and instead to ponder the exploding cascade of fuzz guitar machines gunning the bass player's layers of flaming jelly as "Street Fighting Man" closed out the show at the Altamont Raceway in early December 1969.

David and Albert Maysles brought about a dozen cameras (and a young George Lucas) to film the tail end of the Rolling Stones U.S. tour, an event which captured the group shortly after the death of original member Brian Jones as well as at a time when their collective reputations were being plastered as cosmic-demonic.

In a study reported in the February 26, 1998 issue of Nature (Vol. 391, pp. 871-874), researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science conducted a highly controlled experiment demonstrating how a beam of electrons is affected by the act of being observed. The experiment revealed that the greater the amount of "watching," the greater the observer's influence on what actually takes place. This effect may have played a role in the Maysles Brothers' film Gimme Shelter. Heaven knows we wouldn't still be talking about the movie after all these years if Meredith Hunter hadn't had a gun and if the "security" of bikers hadn't stabbed him to death right on camera. Sure, Paul Kantner of the Jefferson Airplane got off a great line at the Angels' expense ("I'd like to mention that the Hells Angels just punched our lead singer and knocked him out for a little while. I'd like to thank them for that."), just as did some well-intentioned woman who was collecting money for the defense of the Black Panther Party when she quipped in all seriousness, "After all, they're just Negroes."

Ultimately, the fact of the film being made added to the horror of Hunter being killed, even though his intentions may have been to snuff Jagger right on camera. I'm suggesting, without intentional humor, that the presence of the cameras on the electrons in attendance may have contributed to the events that the cameras captured. To quote from Nature: "Strange as it may sound, interference can only occur when no one is watching. Once an observer begins to watch the particles going through the openings, the picture changes dramatically: if a particle can be seen going through one opening, then it's clear it didn't go through another. In other words, when under observation, electrons are being 'forced' to behave like particles and not like waves. Thus the mere act of observation affects the experimental findings." Werner Heisenberg formalized the notion that observation affects outcome way back in 1927. Who were the Maysles to prove him wrong?

I can't imagine any of this being an issue upon the film's release in 1970. At that time the group was the most exciting thing going, even if the presence of Tina Turner was simply to masturbate the microphone or if the Flying Burrito Brothers were not captured to decent effect or if Grace Slick proved herself to be an emotional fascist once and for all by becoming an apologist for the bikers.

It's still a great film, despite all the baggage it's been forced to carry over the decades (end of the sixties, end of the innocence, end of "American Pie" song, etc). Jagger looks good critiquing himself as he and the band review the early cuts of the film. The whole process prompted me to ask myself if I would have still enjoyed the movie if I didn't know anything about the group or Melvin Belli or any of that. It's sort of a bullshit proposition, I guess, but I'd like to think I would still love it if for no other reason than the importance of the idea of needing a security force to protect the band from the public that they themselves had energized into becoming a threat.

Oh yeah. The music was nice.

David and Albert Maysles brought about a dozen cameras (and a young George Lucas) to film the tail end of the Rolling Stones U.S. tour, an event which captured the group shortly after the death of original member Brian Jones as well as at a time when their collective reputations were being plastered as cosmic-demonic.

In a study reported in the February 26, 1998 issue of Nature (Vol. 391, pp. 871-874), researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science conducted a highly controlled experiment demonstrating how a beam of electrons is affected by the act of being observed. The experiment revealed that the greater the amount of "watching," the greater the observer's influence on what actually takes place. This effect may have played a role in the Maysles Brothers' film Gimme Shelter. Heaven knows we wouldn't still be talking about the movie after all these years if Meredith Hunter hadn't had a gun and if the "security" of bikers hadn't stabbed him to death right on camera. Sure, Paul Kantner of the Jefferson Airplane got off a great line at the Angels' expense ("I'd like to mention that the Hells Angels just punched our lead singer and knocked him out for a little while. I'd like to thank them for that."), just as did some well-intentioned woman who was collecting money for the defense of the Black Panther Party when she quipped in all seriousness, "After all, they're just Negroes."

Ultimately, the fact of the film being made added to the horror of Hunter being killed, even though his intentions may have been to snuff Jagger right on camera. I'm suggesting, without intentional humor, that the presence of the cameras on the electrons in attendance may have contributed to the events that the cameras captured. To quote from Nature: "Strange as it may sound, interference can only occur when no one is watching. Once an observer begins to watch the particles going through the openings, the picture changes dramatically: if a particle can be seen going through one opening, then it's clear it didn't go through another. In other words, when under observation, electrons are being 'forced' to behave like particles and not like waves. Thus the mere act of observation affects the experimental findings." Werner Heisenberg formalized the notion that observation affects outcome way back in 1927. Who were the Maysles to prove him wrong?

I can't imagine any of this being an issue upon the film's release in 1970. At that time the group was the most exciting thing going, even if the presence of Tina Turner was simply to masturbate the microphone or if the Flying Burrito Brothers were not captured to decent effect or if Grace Slick proved herself to be an emotional fascist once and for all by becoming an apologist for the bikers.

It's still a great film, despite all the baggage it's been forced to carry over the decades (end of the sixties, end of the innocence, end of "American Pie" song, etc). Jagger looks good critiquing himself as he and the band review the early cuts of the film. The whole process prompted me to ask myself if I would have still enjoyed the movie if I didn't know anything about the group or Melvin Belli or any of that. It's sort of a bullshit proposition, I guess, but I'd like to think I would still love it if for no other reason than the importance of the idea of needing a security force to protect the band from the public that they themselves had energized into becoming a threat.

Oh yeah. The music was nice.

And now?

I think we've established 1970 as a watershed year for what was then a very new type of cinema, one which inverted the old notions of propriety and even morality. Violence hurt, by definition. There could be nothing gained by making it appear to feel good, unless it was in an early Roger Corman flick such as Bloody Mama, starring Shelly Winters, Robert DeNiro and Bruce Dern. Corman took all the grace, humanity and even humor from Bonnie and Clyde and regurgitated a ballet of perversion that brought a different kind of culture to the kids in cars at drive-ins up and down the countryside. Bob Rafelson put together a first rate cast that included Jack Nicholson and Karen Black, used the songs of Tammy Wynette as a backdrop and sent his aimless characters crashing into one another with an honesty so sharp that Five Easy Pieces slashed more wicked than a horror film. And of course, then as now, Mike Nichols could be counted on to pander to the tastes of establishment types who wanted to watch a film and walk out into the sunshine with the sense that they were in on the joke, so something such as Catch-22 was right up their hookahs.

If violence hurt, then sex felt good, at least to those who either dreamed of it or got it on their own terms. A young and adventurous Hitchcock fan named Brian DePamla, fresh off the underground success of Greetings two years earlier gave Bob DeNiro yet another early credit with Hi, Mom!, a voyeuristic comedy, just as an aging Luis Bunuel placed the marvelous Fernando Rey against the also marvelous Catherine Deneuve in Tristana, possibly the best foreign film of the year, inverting the promise of socialism with the rationalizations of romance.

Other notable and excellent films of that glorious and trans-formative year (that is, those we haven't addressed earlier) were Little Big Man, M*A*S*H, The Music Lovers, El Topo, The Wild Child, Getting Straight, and See You at Mao. The latter film was directed by Jean-Luc Godard, whom I have idolized ever since I first fell asleep during his brilliant Sympathy for the Devil. The second time I watched it I laughed so hard the neighbors called the police. I've been afraid to watch it a third time, but there's always a chance.

If violence hurt, then sex felt good, at least to those who either dreamed of it or got it on their own terms. A young and adventurous Hitchcock fan named Brian DePamla, fresh off the underground success of Greetings two years earlier gave Bob DeNiro yet another early credit with Hi, Mom!, a voyeuristic comedy, just as an aging Luis Bunuel placed the marvelous Fernando Rey against the also marvelous Catherine Deneuve in Tristana, possibly the best foreign film of the year, inverting the promise of socialism with the rationalizations of romance.

Other notable and excellent films of that glorious and trans-formative year (that is, those we haven't addressed earlier) were Little Big Man, M*A*S*H, The Music Lovers, El Topo, The Wild Child, Getting Straight, and See You at Mao. The latter film was directed by Jean-Luc Godard, whom I have idolized ever since I first fell asleep during his brilliant Sympathy for the Devil. The second time I watched it I laughed so hard the neighbors called the police. I've been afraid to watch it a third time, but there's always a chance.

The film of Bob Dylan's 1966 tour of Britain is not a remake of Don't Look Back, the brilliant and beautiful movie of the English 1965 tour. Just writing those words causes me to suspect you may be wondering about the value of analyzing a remarkably bad film from 1971-72. There actually is a point and we will get to it in short order. Meanwhile, your patience is appreciated.

One thing must be admitted: The film features Dylan at his best looking and at one of the peaks of his artistic talent. This is the period of his three greatest recordings (Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde) and his most artistically successful work. The concert tour took place shortly before Bobby wrecked his motorcycle, an event which laid him up for a spell and kept him off the stage, although not away from music. Somehow or other he got it in his head that it would be nice to edit the film himself, a statement of fact causing more than one person to wonder what horrors were contained in the outtakes.

Because Dylan did have an astute awareness of the power of film--having grown up on Elvis movies and having been a grown-up at the time of A Hard Day's Night--he knew just enough, as they say, to be dangerous. The film takes about ten minutes to move beyond scenes from a van of the English countryside, scenes which probably meant a lot to the farmers and shepherds but not to anyone else.

This is quite simply one of the sloppiest, most literally unfocused films ever involving a major star.

And yet. . .

We get to see and hear four-fifths of the group that would soon become The Band. We get to see and hear Dylan sing a proud and intimate duet with Johnny Cash. We get to endure a tedious yet occasionally interesting car ride with Dylan and John Lennon, both of whom appear to be smashed, although John clearly handles the condition better. But most importantly we get to lay back shaking in awe of two live versions of "Ballad of a Thin Man," the second of which is so vituperative you'd swear the singer had swallowed a bayonet. For the duration of that performance, it is possible to forgive Bob Dylan anything, including the remainder of the movie, which has a running time of 54 minutes but which is nevertheless otherwise interminable.

Some genius at ABC-TV had encouraged the film's production, thinking the network might turn a handy dollar or two on the free-spending youth market. I am certainly not the first person to wonder if the entire cinematic enterprise were intended to be so bad that ABC would reject it--as they in fact did. The best arguments against that theory are (a) Dylan did choose to release the bugger, and (b) artists are driven more by ego than by any other thing. It's entirely possible Bob thought this film was a major statement. After all, he did write the book Tarantula.

Some of the lessons of the 1960s spoke to the dangers of over-indulgence, in one sense meaning that the human form is not invincible, as Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Keith Moon, among others, can attest. In another sense, though, an over-abundance of self-indulgence can be nearly as lethal as a speed ball overdose. This film and its many cousins of that period are visual records of just how deadly dull ego-centrism can be when it's given no guidance whatsoever, unless chemicals count.

A lot of people called the 1966 concerts "The Judas tour," referring to an audience member who shouted that epithet at the stage. Dylan shouts back, "Aw, it's not that bad." Except for the aforementioned song, it actually is.

One thing must be admitted: The film features Dylan at his best looking and at one of the peaks of his artistic talent. This is the period of his three greatest recordings (Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde) and his most artistically successful work. The concert tour took place shortly before Bobby wrecked his motorcycle, an event which laid him up for a spell and kept him off the stage, although not away from music. Somehow or other he got it in his head that it would be nice to edit the film himself, a statement of fact causing more than one person to wonder what horrors were contained in the outtakes.

Because Dylan did have an astute awareness of the power of film--having grown up on Elvis movies and having been a grown-up at the time of A Hard Day's Night--he knew just enough, as they say, to be dangerous. The film takes about ten minutes to move beyond scenes from a van of the English countryside, scenes which probably meant a lot to the farmers and shepherds but not to anyone else.

This is quite simply one of the sloppiest, most literally unfocused films ever involving a major star.

And yet. . .

We get to see and hear four-fifths of the group that would soon become The Band. We get to see and hear Dylan sing a proud and intimate duet with Johnny Cash. We get to endure a tedious yet occasionally interesting car ride with Dylan and John Lennon, both of whom appear to be smashed, although John clearly handles the condition better. But most importantly we get to lay back shaking in awe of two live versions of "Ballad of a Thin Man," the second of which is so vituperative you'd swear the singer had swallowed a bayonet. For the duration of that performance, it is possible to forgive Bob Dylan anything, including the remainder of the movie, which has a running time of 54 minutes but which is nevertheless otherwise interminable.

Some genius at ABC-TV had encouraged the film's production, thinking the network might turn a handy dollar or two on the free-spending youth market. I am certainly not the first person to wonder if the entire cinematic enterprise were intended to be so bad that ABC would reject it--as they in fact did. The best arguments against that theory are (a) Dylan did choose to release the bugger, and (b) artists are driven more by ego than by any other thing. It's entirely possible Bob thought this film was a major statement. After all, he did write the book Tarantula.

Some of the lessons of the 1960s spoke to the dangers of over-indulgence, in one sense meaning that the human form is not invincible, as Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Keith Moon, among others, can attest. In another sense, though, an over-abundance of self-indulgence can be nearly as lethal as a speed ball overdose. This film and its many cousins of that period are visual records of just how deadly dull ego-centrism can be when it's given no guidance whatsoever, unless chemicals count.

A lot of people called the 1966 concerts "The Judas tour," referring to an audience member who shouted that epithet at the stage. Dylan shouts back, "Aw, it's not that bad." Except for the aforementioned song, it actually is.

The creative surge which defined the 1960s spilled over onto the tabletop of foreign and domestic celluloid, one consequence being that the youth culture and all its undisciplined dollars came to properly recognize television as being a prime tool of the Enemy. Television was that thing used by Aaron Spelling to puke up "The Mod Squad," an attempt to co-opt the sincerity of youth rebellion. Television was a series of refusing-to-die westerns such as "Gunsmoke," "Cimarron Strip" and "Bonanza," none of which dared move beyond the cliches of good versus evil. Television was cop shows, medical dramas and situation comedies that either purposefully avoided social relevance or exploited significance for its own vile ends. So, yes, by 1971, television was clearly the domain of the square, the cube, the straight, the unenlightened, the hard hat, the tranquilized housewife, and strictly for those over the age of thirty.

Enter Bud Yorkin and Norman Lear, two wise acres who aimed to change all that. They knew that the television box was inherently capable of doing good. After all, "The Dick van Dyke Show" had been good. "The Twilight Zone" and "Outer Limits" had been good. Good was not out of the question. What was missing was sincerity and relevance.

Bam! 1970. "Til Death Do Us Part" was piloted before an ABC-TV audience. The Archie Justice (later renamed Bunker) character played to perfection by Carroll O'Connor stormed onto the stage as a confirmed bigot. The liberal son-in-law was, in real life, the son of the man behind "The Dick van Dyke Show." Sally Struthers had a nice set and Jean Stapleton was a legitimate actress. And with stories about black people moving in next door, the racial make-up of Jesus, and a homosexual ex-fullback, one could hardly get more relevant.

ABC passed on the show. CBS picked it up the following year and "All in the Family" became the biggest kid on the block, first among the middle-agers and soon enough by young liberals and old conservatives, as well as the other way around. The name Norman Lear became one of the few behind the camera names to break into the public consciousness.

And then a funny thing happened. Time magazine named Archie Bunker its "Man of the Year." That fact put upon the program and its endless spin-offs the mark of left-handed respectability, something that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg were about to do to the new crop of movies influenced by the creativity of the 1960s.

The second funny thing that happened was the release of a Norman Lear movie called Cold Turkey. At a time when very nice people such as Pauline Kael were pronouncing backlash movies like Dirty Harry fascist masterpieces, it was actually the liberal Norman Lear who inadvertently ruined everything with this charming little picture.

The movie's premise was clever enough. An evil tobacco company, looking to enhance its public relations, offers a small Iowa town $25 million for all of its citizens (all 4006 of them) to quit smoking for thirty days. The tobacco company doesn't expect to have to pay off, of course, so their benevolence shouldn't have to cost them anything. The reason the local parson--Dick van Dyke--wants the town to win is so he can get transferred out of what he perceives to be a dying town. The town council wants to win the money so it can build new hospitals, schools and shopping malls, the intent being to lure military contractors to their rustic village. Hypocrisy is the name of the game on all levels and Lear quite correctly perceived that a savvy youth would be hip to the idea of exposing the core hypocrisy inherent in the American class system. The only problem. . .

The only problem was the actors. Without exception, each and every actor in the film was one associated with the generation presumed by youth to be responsible for all the hypocrisy in the first place. Bob Newhart, Jean Stapleton, Bob and Ray and the rest of the cast--among the nicest people one could hope to meet and certainly excellent comedic actors, one and all--were not going to lure Bobby and Rose to the drive-in to watch a movie. And of course, the old folks didn't go see too many movies in 1971, what with musicals changing into things like Cabaret and everything else so fuckin' dirty and damnably violent.

So the movie bombed, leaving a crater the size of Hollywood, dragging half the talent in America down with it. Jesus, if a naturally hilarious plot and ready-made talent in the hands of the biggest name in television couldn't make the transition to movies--

A ha! That was the problem. The transition to movies very seldom works, as the people who made the first Star Trek movie can attest. TV is obvious while motion pictures are subtle. TV has a live spontaneity while movies are polished and refined, however crude the topic. TV has low budgets while movies cost millions. And certain actors, such as the cast of Cold Turkey, are thought of as TV actors and the people at home don't want the two worlds to intermingle.

None of this means that the movie is anything less than wonderful. While certain bits of the comedy are predictable, most of it is still hilarious and the internal ambiance of the town is so exact and accurate it's scary. What it does mean is that the confusion over audience identification doomed the picture while the attempt at making the jump to the big screen not only failed to elevate television, it cast aspersions on movies in general.

I'm not saying Cold Turkey ended the adventurous nature of motion pictures in the 1970s. It would take the aforementioned Lucas and Spielberg to do that. What it did do was put a sizable chink in the armor worn by a creative army of Hollywood and overseas talent. Watching the film today, the humor is still ripe, you still hate the tobacco company, you still hate the clergy and the town council, you still marvel at the genius of Bob and Ray. It's an easy film to digest because there's nothing at all unsettling in the way it is presented. It is that worst of all old style films: safe.

However, whoever had the idea of using Randy Newman's "He Gives Us All His Love" during the opening credits was a genius.

Enter Bud Yorkin and Norman Lear, two wise acres who aimed to change all that. They knew that the television box was inherently capable of doing good. After all, "The Dick van Dyke Show" had been good. "The Twilight Zone" and "Outer Limits" had been good. Good was not out of the question. What was missing was sincerity and relevance.

Bam! 1970. "Til Death Do Us Part" was piloted before an ABC-TV audience. The Archie Justice (later renamed Bunker) character played to perfection by Carroll O'Connor stormed onto the stage as a confirmed bigot. The liberal son-in-law was, in real life, the son of the man behind "The Dick van Dyke Show." Sally Struthers had a nice set and Jean Stapleton was a legitimate actress. And with stories about black people moving in next door, the racial make-up of Jesus, and a homosexual ex-fullback, one could hardly get more relevant.

ABC passed on the show. CBS picked it up the following year and "All in the Family" became the biggest kid on the block, first among the middle-agers and soon enough by young liberals and old conservatives, as well as the other way around. The name Norman Lear became one of the few behind the camera names to break into the public consciousness.

And then a funny thing happened. Time magazine named Archie Bunker its "Man of the Year." That fact put upon the program and its endless spin-offs the mark of left-handed respectability, something that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg were about to do to the new crop of movies influenced by the creativity of the 1960s.

The second funny thing that happened was the release of a Norman Lear movie called Cold Turkey. At a time when very nice people such as Pauline Kael were pronouncing backlash movies like Dirty Harry fascist masterpieces, it was actually the liberal Norman Lear who inadvertently ruined everything with this charming little picture.

The movie's premise was clever enough. An evil tobacco company, looking to enhance its public relations, offers a small Iowa town $25 million for all of its citizens (all 4006 of them) to quit smoking for thirty days. The tobacco company doesn't expect to have to pay off, of course, so their benevolence shouldn't have to cost them anything. The reason the local parson--Dick van Dyke--wants the town to win is so he can get transferred out of what he perceives to be a dying town. The town council wants to win the money so it can build new hospitals, schools and shopping malls, the intent being to lure military contractors to their rustic village. Hypocrisy is the name of the game on all levels and Lear quite correctly perceived that a savvy youth would be hip to the idea of exposing the core hypocrisy inherent in the American class system. The only problem. . .

The only problem was the actors. Without exception, each and every actor in the film was one associated with the generation presumed by youth to be responsible for all the hypocrisy in the first place. Bob Newhart, Jean Stapleton, Bob and Ray and the rest of the cast--among the nicest people one could hope to meet and certainly excellent comedic actors, one and all--were not going to lure Bobby and Rose to the drive-in to watch a movie. And of course, the old folks didn't go see too many movies in 1971, what with musicals changing into things like Cabaret and everything else so fuckin' dirty and damnably violent.

So the movie bombed, leaving a crater the size of Hollywood, dragging half the talent in America down with it. Jesus, if a naturally hilarious plot and ready-made talent in the hands of the biggest name in television couldn't make the transition to movies--

A ha! That was the problem. The transition to movies very seldom works, as the people who made the first Star Trek movie can attest. TV is obvious while motion pictures are subtle. TV has a live spontaneity while movies are polished and refined, however crude the topic. TV has low budgets while movies cost millions. And certain actors, such as the cast of Cold Turkey, are thought of as TV actors and the people at home don't want the two worlds to intermingle.

None of this means that the movie is anything less than wonderful. While certain bits of the comedy are predictable, most of it is still hilarious and the internal ambiance of the town is so exact and accurate it's scary. What it does mean is that the confusion over audience identification doomed the picture while the attempt at making the jump to the big screen not only failed to elevate television, it cast aspersions on movies in general.

I'm not saying Cold Turkey ended the adventurous nature of motion pictures in the 1970s. It would take the aforementioned Lucas and Spielberg to do that. What it did do was put a sizable chink in the armor worn by a creative army of Hollywood and overseas talent. Watching the film today, the humor is still ripe, you still hate the tobacco company, you still hate the clergy and the town council, you still marvel at the genius of Bob and Ray. It's an easy film to digest because there's nothing at all unsettling in the way it is presented. It is that worst of all old style films: safe.

However, whoever had the idea of using Randy Newman's "He Gives Us All His Love" during the opening credits was a genius.

There are those who will tell you that Get Carter ranks as one of the worst films ever made, by which they mean the 1971 Mike Hodges original rather than the 2000 Sylvester Stallone remake, in which case, if those folks who say it were talking about the latter they might actually have a point. The original, however, is very much something else again and should not be missed, even if the story-line does leave the novice wondering what the bleeding hell is going on.

What is going on is that Michael Caine proves himself to be one of the world's finest actors. If one of the reasons you go to movies is to witness great acting, then you've been disappointed of late. But if that is one of the reasons, Get Carter will win you over immediately. Notice how Caine casts his glance at the telephone when the other party has hung up. Notice how he stares at one woman while seducing another over the phone. Notice the title of the book he's reading on the train reinforces our misperception of his character's real occupation.

It's a brilliant film that several folks thought was immoral and they thought this primarily because of the convincing performance Caine delivers. If Caine had sucked in it the way Stallone did in the remake, no one would have cared that a bad guy appeared to be getting glorified. In other words, forget Alfie and even forget Dressed to Kill. Get Carter instead. You won't like it, but you will love it.

Why will you love it and how can I know? Aside from exploiting the audience's preconceived notions that Jack Carter is a P.I.--which he isn't--the film makes great use of low angle shots from what feels like beneath the floor and even gives a sense of the English town of Newcastle grit that I'm willing to bet didn't make it into the Chamber of Commerce brochures. Oh, yes, and Britt Ekland appears in the film as Anna, Carter's niece She's quite young and either vulnerable or tough as nails--it's hard to say which.

There's a part of me that hopes this film is your first exposure to Mr. Caine, unlikely as that may be. If it is, everything else you see him in will be measured against this performance, one of his very best, which is to say, one of the best of anyone.

What is going on is that Michael Caine proves himself to be one of the world's finest actors. If one of the reasons you go to movies is to witness great acting, then you've been disappointed of late. But if that is one of the reasons, Get Carter will win you over immediately. Notice how Caine casts his glance at the telephone when the other party has hung up. Notice how he stares at one woman while seducing another over the phone. Notice the title of the book he's reading on the train reinforces our misperception of his character's real occupation.

It's a brilliant film that several folks thought was immoral and they thought this primarily because of the convincing performance Caine delivers. If Caine had sucked in it the way Stallone did in the remake, no one would have cared that a bad guy appeared to be getting glorified. In other words, forget Alfie and even forget Dressed to Kill. Get Carter instead. You won't like it, but you will love it.

Why will you love it and how can I know? Aside from exploiting the audience's preconceived notions that Jack Carter is a P.I.--which he isn't--the film makes great use of low angle shots from what feels like beneath the floor and even gives a sense of the English town of Newcastle grit that I'm willing to bet didn't make it into the Chamber of Commerce brochures. Oh, yes, and Britt Ekland appears in the film as Anna, Carter's niece She's quite young and either vulnerable or tough as nails--it's hard to say which.

There's a part of me that hopes this film is your first exposure to Mr. Caine, unlikely as that may be. If it is, everything else you see him in will be measured against this performance, one of his very best, which is to say, one of the best of anyone.

You can take your Eugene Ionesco, Jean Genet, and even your Samuel Beckett and I will still stand by Jules Feiffer as the preeminent absurdist playwright of our era based on the power of Little Murders, a power which the passage of time has only served to intensify. Released in 1971 and based on the 1967 play of the same name, this movie knocks you down from the first frame and never lets up. From a recurring obscene phone caller to the eloquent brutality of lines delivered by Elliott Gould, Marcia Rudd and Vincent Gardena, from the silent commentary direction of Alan Arkin to the stammering soliloquy of the same Arkin, as well as a thoroughly brain-busting performance by Donald Sutherland as a minister, this movie is absurd for reasons other than for the sake of absurdity, which is usually good enough. The insanity of our own existences has left us unable to perceive their ridiculous essences and so this motion picture would have had to create Jules Feiffer if he hadn't created it first.

Elliott Gould was the only actor from the original Broadway play to make the transition to the film and watching him here shows the wisdom of that decision. He enriches every line--even the ones that seem to be throwaways, like "I'm not a good debater," with amazing strength that draws in the audience's empathetic tendencies, especially when Marcia Rudd tells him she married him so she could change him and mold him.

I realize that certain schizophrenics out there more married to exactness than creativity will take issue with me calling this film absurdist. I don't care. Those who do take such issue are probably accustomed to being wrong. Little Murders is absurdist specifically because it takes the internal logic of human beings and exposes that for the emotionally-based cowardice that it usually is fronting for. I guarantee you this: After watching this movie, you will experience the world in which you most likely vegetate in an entirely different way. About how many of today's films can you say that? Imagine getting changed--or even excited--by Avatar or Sherlock fucking Holmes! That is why all blockbusters and/or star-infested films are de facto bullshit scum slime, including several that I actually enjoy. They do not try to change you, they do not want to change you, and they indeed do not change you. I want to emerge from the cinema a screaming psychopath, a raving beast who for the first time in his stinking miserable pot-piss of a life actually sees things for the way they are. Fuck movies! Any imbecile can make a fucking film. When you make something that alters the way we look at everything else, then, my sons and daughters, you have genuinely accomplished something worth talking about. Jules Feiffer did that with Carnal Knowledge (and despite Mike Nichols). He did it with Little Murders with the help of Alan Arkin. Buy it, download it, steal it. I don't care how you acquire it. Just do it. You can thank me later.

One of the things I've intended to do with the website known as Philropost is to write about the brilliant person known as Elaine May. People of a certain age may have first become aware of her tremendous talents when she was paired with another future writer-director, a fellow named Mike Nichols. Back then the comedy-duo were known as Nichols and May. Rather than tell jokes, they performed sketches of life's more awkward moments. They were amazing.

Since her "solo" career began in the mid-1960s, she has worked as an actor, a writer and a director, some of her finer credits being having written the screenplay for the remake of Heaven Can Wait, her work on the script for Reds, and her writing for The Birdcage and Primary Colors. Her low point, and it was pretty low, was her involvement in Ishtar, about which the less said the better.

One of the best things she ever did--and one that people sometimes forget--is her writing and acting credit on a fantastic little gem of a film that came out in 1971. The film, A New Leaf, starred herself and Walter Matthau. Matthau plays Henry, a pseudo-aristocrat who has squandered his wealth. May plays Henrietta, a smart and clumsy woman who has more wealth than she can spare and a great deal of bookish interests which she yearns to share. The genius of the movie--aside from the stark and gorgeous acting of the two leads--is how Elaine wrote the scenes so that the inner workings of both leads' characters seep out so slowly that we hardly realize it has happened.

What with Henry's despicable personal history, his horrible haircut and his ugly double-breasted suits, he is primed to be roundly despised by the audience. The only reason he is not is because he comes to Henrietta's psychological defense even as he is planning to manipulate her into a marriage that will presumably rescue him from his financial woes. May plays the struggling klutz with brains to absolute perfection just as Matthau plays the worthwhile cad. The denouement works but doesn't annoy or surprise (as often happens in screen comedies) because it is thoroughly uncontrived. Everyone in this film is stellar, including a young Doris Roberts, a woman who acted in many of the early-seventies smashes we've been discussing lately.

Since her "solo" career began in the mid-1960s, she has worked as an actor, a writer and a director, some of her finer credits being having written the screenplay for the remake of Heaven Can Wait, her work on the script for Reds, and her writing for The Birdcage and Primary Colors. Her low point, and it was pretty low, was her involvement in Ishtar, about which the less said the better.

One of the best things she ever did--and one that people sometimes forget--is her writing and acting credit on a fantastic little gem of a film that came out in 1971. The film, A New Leaf, starred herself and Walter Matthau. Matthau plays Henry, a pseudo-aristocrat who has squandered his wealth. May plays Henrietta, a smart and clumsy woman who has more wealth than she can spare and a great deal of bookish interests which she yearns to share. The genius of the movie--aside from the stark and gorgeous acting of the two leads--is how Elaine wrote the scenes so that the inner workings of both leads' characters seep out so slowly that we hardly realize it has happened.

What with Henry's despicable personal history, his horrible haircut and his ugly double-breasted suits, he is primed to be roundly despised by the audience. The only reason he is not is because he comes to Henrietta's psychological defense even as he is planning to manipulate her into a marriage that will presumably rescue him from his financial woes. May plays the struggling klutz with brains to absolute perfection just as Matthau plays the worthwhile cad. The denouement works but doesn't annoy or surprise (as often happens in screen comedies) because it is thoroughly uncontrived. Everyone in this film is stellar, including a young Doris Roberts, a woman who acted in many of the early-seventies smashes we've been discussing lately.

This story and the filmed visualization of it will stay with you for several days, tugging at you to want to watch it again, and that's a good reason to request the bloody thing to be issued on DVD. I've no idea how such a request is to be made, but I urge those of you who do know such matters to get on it right away. Elaine May is a national treasure, as much a bedrock of American comedy as Lily Tomlin and her acting blows the wind out of the sails of far lesser performers such as the truly vile Sarah Silverman. If you need a point of reverence, the genuine comedy of a show like "30 Rock" would be unimaginable without Elaine May having prepared the stages for it.

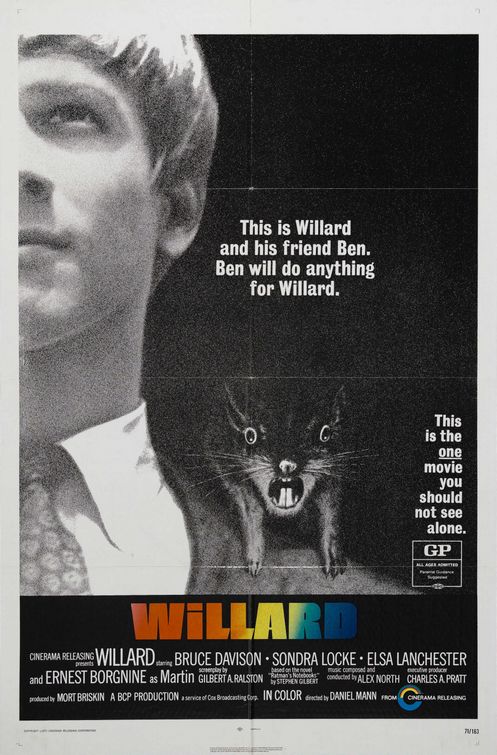

These days they'd dress the story up so that the nerdy kid came across the way of Napoleon Dynamite (I'm still waiting for Moron TV to get sued by Elvis Costello for stealing the name) so that he was the butt of the joke rather than the cause of the conflict. But these were the good days, the days when bourgeois falsity in the form of employers and parents and co-workers got righteously slammed and slammed for good. They were the establishmentarians and the misfits had the responsibility of bringing the bastards down, which is how we ended up with the outstanding Brian DePalma film Carrie, a film that Willard does not much resemble. So even though the movie about the young man with a friend named Ben who is a rat was marketed as a revenge-seeking horror film, that fact does not really excuse the making of a sequel (Ben), much less a remake of the original in 2003.

Look, the sound isn't very good, Bruce Davison is only slightly above average in the acting department, and Sondra Locke (the best thing in the film) went on to be in a bunch of Eastwood movies, plus the damned flick just wasn't all that scary. It even occasionally came across as if it were being directed by a bunch of effete English snobs, but it didn't even have that saving grace. Creepy? Yes. Scary? No. Hey, I like watching Ernest Borgnine being eaten by rodents as much as the next guy, but the sight does not exactly frighten me, y' know?

Look, the sound isn't very good, Bruce Davison is only slightly above average in the acting department, and Sondra Locke (the best thing in the film) went on to be in a bunch of Eastwood movies, plus the damned flick just wasn't all that scary. It even occasionally came across as if it were being directed by a bunch of effete English snobs, but it didn't even have that saving grace. Creepy? Yes. Scary? No. Hey, I like watching Ernest Borgnine being eaten by rodents as much as the next guy, but the sight does not exactly frighten me, y' know?

If it's a scary 1971 movie that you want, try Duel. Starring Dennis Weaver (McCloud, Gunsmoke), this is one of the most mesmerizingly intense experiences you are likely to endure and you will love it from start to finish.

Chances are you've heard a bit about Steven Spielberg's first directorial effort. You may have even heard that it was great. It was beyond great. And the story is as simple as mud. Dennis Weaver is driving across country while on the job and some crazy-ass truck driver decides to do him in, pitting semi against Plymouth Valiant. There's really nothing more to it than that, which is kind of like saying Romeo and Juliet is just a damned love story. Weaver turns in the performance of a life time here and Spielberg was seldom better--and after Jaws he never was better. The sense of being on the road, of being behind the wheel, of having a deranged giant mated to your destruction--these elements are captured, conveyed and transmogrified on the screen with such steadily increasing terror that you might not even notice the clever subtleties, such as the hash marks on the bumper of the 18-wheeler. This movie is Hitchcock on a lifeboat, this movie is John Ford on the prairie, this is Walter Huston in the mountains. This is life and death, the way movies were supposed to be and I guarantee you that you'll think twice before cutting off a semi again.

What both this film and Willard share is an enormous distrust for the powers that be, just as things used to be and one day will be again, just as soon as Costello really does sue those MTV monsters. In Willard's case, it's his mom, his boss, his co-workers, the girl he likes--everything is subject to either going away or betraying him, just as his father's company was stolen out from under him. In the case of Dennis Weaver, the enemy is Goliath of the Philistines, a mindless driver who intends to destroy him simply because he exists. This isn't karma bullshit. In other words, the doom isn't facing Weaver because he cheats on his wife or steals from his company. The doom comes after him because that is what doom does, just like a war on the loose.

Chances are you've heard a bit about Steven Spielberg's first directorial effort. You may have even heard that it was great. It was beyond great. And the story is as simple as mud. Dennis Weaver is driving across country while on the job and some crazy-ass truck driver decides to do him in, pitting semi against Plymouth Valiant. There's really nothing more to it than that, which is kind of like saying Romeo and Juliet is just a damned love story. Weaver turns in the performance of a life time here and Spielberg was seldom better--and after Jaws he never was better. The sense of being on the road, of being behind the wheel, of having a deranged giant mated to your destruction--these elements are captured, conveyed and transmogrified on the screen with such steadily increasing terror that you might not even notice the clever subtleties, such as the hash marks on the bumper of the 18-wheeler. This movie is Hitchcock on a lifeboat, this movie is John Ford on the prairie, this is Walter Huston in the mountains. This is life and death, the way movies were supposed to be and I guarantee you that you'll think twice before cutting off a semi again.

What both this film and Willard share is an enormous distrust for the powers that be, just as things used to be and one day will be again, just as soon as Costello really does sue those MTV monsters. In Willard's case, it's his mom, his boss, his co-workers, the girl he likes--everything is subject to either going away or betraying him, just as his father's company was stolen out from under him. In the case of Dennis Weaver, the enemy is Goliath of the Philistines, a mindless driver who intends to destroy him simply because he exists. This isn't karma bullshit. In other words, the doom isn't facing Weaver because he cheats on his wife or steals from his company. The doom comes after him because that is what doom does, just like a war on the loose.

When I first saw Robert Benton's Bad Company way back in 1972, I was simultaneously mesmerized and offended. I was mesmerized by the story of a group of young males on the lam from Civil War-era conscription and by the sawed-off shimmer of Jeff Bridges' character Jake. What offended me then was the casual aspect of the barbarism as, for instance, when the group of young men and boys shoots a wild rabbit for food or when they slaver for a taste of poontang. Of course, I was quite young at the time and I suppose I was easily abused. These days the fight scenes and casual criminality wouldn't startle a five-year-old and I'm actually a little embarrassed by the prudish aspects of my own earlier response.